The Role of Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine, Their Applications in Dentistry and Orthodontics

Karadede Unal B1* and Karadede MI2

1DDS, PhD of Orthodontics, PhD of Histology and Embriology, Assoc. Prof. Dr. İzmir Katip Çelebi University, Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Orthodontics, İzmir-Türkiye

2DDS, PhD of Orthodontics, PhD of Histology and Embriology, Prof. Dr. İzmir Katip Çelebi University, Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Orthodontics, İzmir-Türkiye

*Corresponding author: Karadede Unal B, DDS, PhD of Orthodontics, PhD of Histology and Embriology, Assoc. Prof. Dr. İzmir Katip Çelebi University, Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Orthodontics, İzmir-Türkiye

Citation: Unal BK, Karadede MI. The Role of Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine, Their Applications in Dentistry and Orthodontics. J Stem Cell Res. 6(1):1-10.

Received: December 23, 2024 | Published: January 10, 2025

Copyright© 2025 genesis pub by Unal BK, et al. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED. This is an open-access article distributedunder the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International License.This allows others distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as they credit the authors for the original creation.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.52793/JSCR.2025.6(1)-67

Abstract

Introduction: Stem cells, particularly mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), possess unique self-renewal and multipotent differentiation capabilities, making them critical to regenerative medicine. MSCs are primarily derived from bone marrow but are also found in adipose tissue, umbilical cord blood, placenta, and exfoliated deciduous teeth. These cells play a vital role in tissue homeostasis and repair, although their abundance diminishes with age and health status. Characterized by their heterogeneity, MSCs secrete bioactive molecules such as IL-6, GM-CSF, and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), contributing to hematopoiesis and immune modulation. Advances in tissue engineering highlight their potential in various medical and dental applications.

General Information: In medicine, MSCs have demonstrated significant potential in treating ischemic conditions, chronic wounds, and osteoarticular disorders through their anti-inflammatory and angiogenic effects. Umbilical cord blood-derived MSCs are particularly effective in regenerative therapies for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and myocardial infarction. In dentistry, MSC-based strategies aim to regenerate periodontal tissues and alveolar bone.

Periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs), a subclass of MSCs, are pivotal during orthodontic treatments, modulating bone remodeling and collagen production under mechanical forces. Additionally, innovative approaches such as low-magnitude, high-frequency vibrations enhance PDLSC differentiation, expediting orthodontic procedures. Emerging technologies like 3D culture systems and bioengineered organoids enable precise modeling of dental tissues, fostering advances in regenerative dentistry.

Conclusion: MSCs offer transformative potential in regenerative medicine and dentistry, addressing critical challenges in tissue repair and restoration. Their ability to modulate inflammation and promote angiogenesis positions them as key players in personalized therapies. Combining MSCs with biomaterials and bioengineering technologies promises innovative solutions for complex medical and dental defects. Ongoing research into their molecular mechanisms and clinical applications will expand their therapeutic scope, making them indispensable in the evolving landscape of regenerative medicine.

Keywords

Particularly Mesenchymal Stem Cells; Umbilical Cord Blood; Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth; Amniotic Fluid

Introduction

Stem cells have a unique place in biology with their ability to self-renew and differentiate into specific cell types. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) represent a class of cells that are found in the bone marrow along with hematopoietic stem cells, but are not hematopoietic. While bone marrow is the primary source of MSCs, they have also been identified in tissues such as adipose tissue, umbilical cord blood, chorionic villi of the placenta, amniotic fluid, peripheral blood, fetal liver and deciduous teeth. These cells vary in quantity depending on factors such as aging and general health status. While the highest density is seen in newborns, this amount gradually decreases throughout life and halves by the age of 80 [1-11].

MDCs are a heterogeneous population in terms of morphology, physiology and surface antigens. No specific marker for these cells has yet been identified, but it is known that in the bone marrow stroma, MSCs express many biomolecules such as adhesion molecules, extracellular matrix proteins, cytokines and growth factor receptors. For example, they secrete proteins such as fibronectin, laminin and proteoglycan. They also contribute to the regulation of hemopoiesis by producing hemopoietic and non-hemopoietic growth factors. The molecules they secrete include IL-1, IL-6, IL-7, GM-CSF, SCF and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [8,12-16]. These cells are located in specialized areas known as stem cell niches and are usually in a quiescent state. However, stimuli such as injury or disease can activate their self-renewal capacity. After leaving their niches, they join the circulation and migrate to target tissues. During this migration, they can initiate differentiation processes depending on microenvironmental stimuli. For example, studies in murine models have shown that circulating MSCs can migrate to various tissues and colonize them [17-20].

The differentiation potential of MDCs was initially considered limited to mesodermal cells. However, recent studies have shown that they can differentiate into various cell lineages such as osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, myoblasts and even neurons. This differentiation is thought to result from reprogramming in gene expression or the effect of certain soluble factors (8,21-24).

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and adult stem cells constitute the two main classes of stem cells. ESCs are pluripotent cells derived from embryos at the blastocyst stage and form the three basic germ layers during embryonic development. Adult stem cells, in contrast, are specific to specific tissues and are usually classified as multipotent. Multipotent stem cells can differentiate into a limited number of cell types. For example, mesenchymal stem cells can show osteogenic, chondrogenic and adipogenic differentiation [25-27].

Umbilical cord blood (UCB) is a rich source of many cell types such as hematopoietic progenitor cells, multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and endothelial progenitor cells. The regenerative effects of umbilical cord blood cells show promise in improving many clinical conditions, from ischemic diseases to osteomuscular disorders. Positive effects of umbilical cord blood cells have been demonstrated in conditions such as hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, stroke and myocardial infarction [27-34]. Tissue engineering aims to regenerate damaged tissues through in vitro manipulation of stem cells and their combination with biomaterials. Stem cell-based approaches for the regeneration of periodontal tissues and the treatment of alveolar bone loss are of particular importance for dentistry. For example, bone loss due to periodontal diseases may not be completely reversed by conventional treatment methods. However, the use of stem cells may make it possible to reconstruct these tissues [35-39].

As a consequence, not only do they provide mechanical support in the bone marrow microenvironment, but also play a critical role in the regulation of hemopoietic processes and tissue regeneration. Emerging molecular techniques provide a deeper understanding of the biological functions of these cells, creating new therapeutic opportunities in the fields of regenerative medicine and tissue engineering [8,40].

Applications of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Medical Therapies

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) represent a class of cells that are present in the bone marrow along with hematopoietic stem cells, but are not hematopoietic. While bone marrow is the primary source of MSCs, their presence has also been described in tissues such as adipose tissue, umbilical cord blood, chorionic villi of the placenta, amniotic fluid, peripheral blood, fetal liver, lungs and deciduous teeth. Studies on the presence of MSCs reveal that these cells show a wide distribution and their therapeutic potential is gradually increasing [1-8]. However, the amount of these cells decreases with aging and general health status. For example, whereas the density of MSCs is highest in newborns, this amount gradually decreases throughout life and halves by the age of 80 [9,10]. On the other hand, fetal MDCs reach the highest density in the circulation in the first trimester and gradually decrease in the following periods [11].

MSCs represent a heterogeneous population in terms of morphology and physiologic properties and no specific marker has yet been identified that identifies these cells. Instead, MDCs express a variety of biomolecules present in the bone marrow stroma, such as adhesion molecules, extracellular matrix proteins, cytokines and growth factor receptors. These cells secrete proteins such as fibronectin, laminin, collagen and proteoglycan and also contribute to the regulation of hemopoiesis by producing hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic growth factors. Among the molecules they secrete are IL-1α, IL-6, GM-CSF and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [8,12-16] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Bone marrow derived MSCs. Cells were cultured in MesenCult Basal Medium for three passages and then differentiation was started. A - Cultured MSCs; B - MSCs after 20 days of osteogenic differentiation (alkaline phosphatase staining); C - MSCs after 20 days of adipogenic differentiation (note adipocytes containing lipid droplets) (8).

MSCs are located in specialized regions known as stem cell niches and are usually found in a quiescent state. However, they can activate their self-renewal capacity after stimuli such as injury, disease or aging [17]. After leaving their niches, they join the circulation and migrate to target tissues. In this process, they can initiate differentiation programs depending on micro environmental conditions. For example, studies in murine models have shown that circulating MSCs can migrate to various tissues and colonize these tissues [18-20].

Initially, it was thought that MSCs could only differentiate into mesodermal cells. However, recent studies have revealed that they have the ability to differentiate into various cell lineages such as osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, myoblasts and even neurons. This differentiation process is thought to occur through reprogramming of gene expression or under the influence of certain soluble factors [8, 21-24]. MDCs have a remarkable potential in medical therapies due to their versatile differentiation potential and immunomodulatory properties. Umbilical cord blood (UCB), an important source of MDCs, is rich in hematopoietic progenitor cells, multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and endothelial progenitor cells. The regenerative effects of GCT have shown promise in improving many clinical conditions, from ischemic diseases to musculoskeletal disorders. Positive effects of GCT cells have been proven in conditions such as hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, stroke and myocardial infarction [27-34].

In addition to their role in regenerative therapies, MDCs also play an active role in the regulation of hematopoiesis. They modulate inflammation and promote angiogenesis by secreting biologically active molecules. These properties are particularly important in the treatment of chronic wounds and in increasing vascularization in ischemic tissues. The ability of MSCs to integrate into damaged tissues and secrete reparative factors makes them an indispensable element of regenerative medicine [8,40].

In addition, MDCs also have important applications in the field of tissue engineering. These cells can be combined with biomaterials to reconstruct damaged tissues. For example, bone marrow-derived MSCs have been used to repair bone defects and heal periodontal tissues. Such approaches have been particularly effective in the regeneration of alveolar bone and craniofacial tissues, offering minimally invasive alternatives to traditional grafting techniques [35-39]. The adaptive abilities of MDCs are not limited to structural support. In clinical and experimental studies, these cells have been shown to regulate inflammation and promote angiogenesis by secreting growth factors and cytokines. These properties are particularly valuable in chronic wound healing and in promoting vascularization. This critical role of MDCs in immune response and tissue repair suggests the potential for their wider use in medical therapies [8, 40].

In conclusion, MDCs have an important place in the field of regenerative therapies and cellular medicine. Their ability to differentiate into different cell types and regulate immune responses has made them a critical resource in the treatment of various medical conditions. Advances in molecular and genetic techniques will further increase the therapeutic potential of MDRs and offer innovative solutions to complex medical problems [8,40].

Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Dentistry and Orthodontic Applications

Stem cells play an important role in tissue engineering strategies to regenerate or replace damaged, diseased or missing tissues and organs. This process occurs through in vitro manipulation of cells and the design of the extracellular environment. In dentistry, tissue engineering is considered a promising field for the regeneration of missing oral tissues or organs. For example, different degrees of alveolar bone loss can occur after tooth extraction due to periodontal diseases, severe caries, root fractures or traumatic tooth loss. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Alveolar bone resorption. (A) Resorption of the labial bone plate in the maxillary anterior occurs after tooth extraction. Alveolar bone augmentation is required to place the dental implant. (B) Some alveolar bone resorption inevitably occurs after tooth loss (black arrow). The posterior alveolar ridge areas in the mandible (white arrows) are flattened by bone resorption after tooth loss. (40)

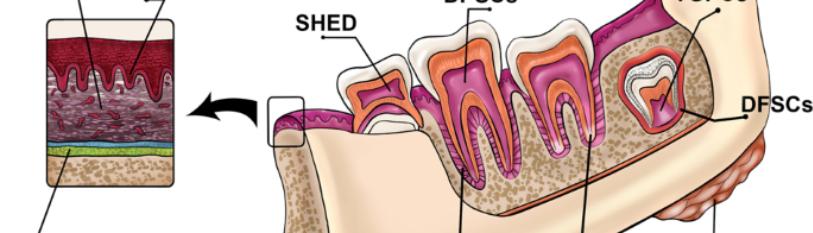

In addition, continuous bone resorption occurs in the mandible in edentulous patients, making dental implant applications difficult [35-39]. Tissues targeted by regenerative medicine strategies in dentistry include structures such as periodontal tissues, alveolar bone, salivary glands and temporomandibular articular cartilage. In particular, easily accessible cells such as gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells (GMSCs) offer promising sources for periodontal regeneration and repair of large bone defects. Stem cells derived from dental tissues include several cell types such as dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs), periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs) and apical papilla stem cells (SCAPs) (Figure 3). These cells are characterized by their high proliferation capacity and stable morphology [40-44].

Figure 3: Sources of adult stem cells in the oral and maxillofacial region (40).

In recent years, the association of periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs) with mechanical loads has attracted attention. During orthodontic treatment, PDLSCs contribute to the remodeling of bone and periodontal tissues by regulating osteogenic differentiation processes at sites of tension and compression. For example, PDLSCs increase the production of osteogenic markers (such as Runx2) and other proteins associated with bone formation in response to mechanical forces. However, it is known that prolonged and high intensity mechanical forces may lead to bone loss by increasing osteoclastogenesis. Therefore, PDLSCs have great potential as a therapeutic tool in orthodontic treatment processes. [45-49]. (Figure 4,5).

Figure 4: Applications of stem cells in dentofacial orthopedics (50)

Figure 5: Possible applications of stem cells (alone or in conjugation with bone scaffolds) in orthodontics (50).

Orthodontic relapse is defined as the tendency of teeth to return to their former position after treatment and PDLSCs play an important role in this process. In particular, their role in Type I collagen production and reorganization of the periodontal ligament makes them a potential target for relapse prevention. Furthermore, it has been found that low magnitude, high frequency vibrations (LMHF) can positively affect the osteogenic differentiation processes of PDLSCs, and it has been shown that such biomechanical stimuli can accelerate tooth movement and increase post-treatment stability [49,50].

Another important potential of stem cells in dentistry is 3D culture environments and bioengineering approaches. These methods can enhance the regenerative potential of stem cells by mimicking the natural environment of dental tissues. For example, structures derived from dental epithelial stem cells, called dentospheres, allow cells to be manipulated while retaining their stem cell properties. In addition, bioengineered dental organoids are among the promising approaches to restore missing teeth in harmony with natural tissues [48]. Stem cells accelerate healing and regeneration by secreting factors like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which promotes angiogenesis and enhances tissue recovery. Studies have shown faster osteogenesis in models using MSCs. Root resorption, a common orthodontic issue, may be mitigated by preemptive use of odontoblast-derived MSCs or dental follicular stem cells (DFSCs). These cells assist in tissue repair and regeneration [47].

Conclusion

In conclusion, regenerative therapies based on stem cells, especially mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), are gaining a great deal of importance in dentistry in terms of periodontal tissue repair, regeneration of the alveolar bone, and orthodontic treatment, advancing processes and preventing relapse. These advances hold new promises for bioengineering and 3D culture techniques in generating natural regeneration of teeth and oral tissues. Continuous research exposes its biological potential for more effective clinical applications. MSCs have great potential in regenerative interventions in dentistry. They are useful in periodontal tissue repair and regeneration of the alveolar bone, as well as in orthodontic treatment, speeding up processes and prevention of relapse. The technology goes a step further in bioengineering and the 3D culture approach, enhancing the potential of such cells for their natural regeneration in teeth and oral tissues. In the future perspective, advances in molecular biology and genetic engineering are predicted to make stem cell-based therapies safer and more effective. Furthermore, personalized treatment approaches and biomimetic tissue engineering methods will accelerate the clinical integration of stem cells. All these advances will enable stem cells to be used more widely and successfully in dentistry and other disciplines.

References

- Gronthos S, Franklin DM, Leddy HA, Robey PG and Storms RW et al (2001). Surface protein characterization of human adipose tissue-derived stromal cells. J Cell Physiology. 189(1);54-63.

- Igura K, Zhang X, Takahashi K, Mitsuru A and Yamaguchi S, et al. (2004). Isolation and characterization of mesenchymal progenitor cells from chorionic villi of human placenta. Cytotherapy. 6(6);543-553.

- Tsai MS, Lee JL, Chang YJ, and Hwang SM. (2004). Isolation of human multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from second-trimester amniotic fluid using a novel two-stage culture protocol. Human Reproduction. 19(6); 1450-1456.

- Zvaifler NJ, Marinova-Mutafchieva L, Adams G, Edwards CJ and Moss J, et al. (2000). Mesenchymal precursor cells in the blood of normal individuals. Arthritis Res. 2(6), 477-488.

- In 't Anker PS, Noort WA, Scherjon SA, Kleijburg-van der Keur C and Kruisselbrink AB, et al. (2003) Mesenchymal stem cells in human second-trimester bone marrow, liver, lung, and spleen exhibit a similar immunophenotype but a heterogeneous multilineage differentiation potential. Haematologica. 88(8):845-852.

- Campagnoli C, Roberts IA, Kumar S, Bennet PR and Bellantuono I, et al. (2001) Identification of mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells in human first-trimester fetal blood, liver, and bone marrow. Blood. 98(8):2396-2402.

- Miura M, Gronthos S, Zhao M, Lu B and Fisher LW, et al. (2003) SHED: stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 100(10):5807-12.

- Bobis S, Jarocha D, and Majka M. (2006) Mesenchymal stem cells: characteristics and clinical applications. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 44(4):215-230.

- Inoue K, Ohgushi H, Yoshikawa T, Okumura M and Sempuku T et al. (1997). The effect of aging on bone formation in porous hydroxyapatite: Biochemical and histological analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 12(6):989-994.

- Fibbe WE, and Noort WA. (2003) Mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells transplantation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 996(1):235-244.

- Campagnoli C, Roberts IA, Kumar S, Bennet PR and Bellantuono I, et al. (2001). Identification of mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells in human first-trimester fetal blood, liver, and bone marrow. Blood. 98(8):2396-2402.

- Devine SM and Hoffman R. (2000) Role of mesenchymal stem cell in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Curr Opin Hematol. 7(6):358-363.

- Jeong JA, Hong SH, Gang EJ, Ahn C and Hwang SH, et al. (2005). Differential gene expression profiling of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells by DNA microarray. Stem Cells. 23(5):584-593.

- Silva WA, Covas DT, Panepucci RA, Proto-Siqueira R and Siufi JL, et al. (2003) The profile of gene expression of human marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 21(6):661-669.

- Boiret N, Rapatel C, Veyrat-Masson R, Guillouard L and Guérin JJ et al. (2005) Characterization of nonexpanded mesenchymal progenitor cells from normal adult human bone marrow. Exp Hematol. 33(2):219-225.

- Colter DJ, Sekiya I, and Prockop DJ. (2001) Identification of a subpopulation of rapidly self-renewing and multipotential adult stem cells in colonies of human marrow stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 98(14):7841-7845.

- Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK and Douglas R, et al. (1999) Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 284(5411):143-147.

- Gao J, Dennis JE, Muzic RF, Lundberg M, and Caplan AI. (2001) The dynamic in vivo distribution of bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells after infusion. Cells Tissues Organs. 169(1):12-20.

- Watt FM, and Hogan BL. (2000) Out of Eden: stem cells and their niches. Science. 287(5457):1427-1430.

- Fernandez M, Simon V, Herrera G, Cao C and Del Favero H, et al. (1997) Detection of stromal cells in peripheral blood progenitor cell collections from breast cancer patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 20(4):265-271.

- Dennis JE, Merriam A, Awadallah A, Yoo JU and Johnstone B, et al. (1999) A quadripotential mesenchymal progenitor cell isolated from the marrow of an adult mouse. J Bone Miner Res. 14(5):700-709.

- Bruder SP, Jaiswal N, and Haynesworth SE. (1997) Growth kinetics, self-renewal, and the osteogenic potential of purified human mesenchymal stem cells during extensive subcultivation and following cryopreservation. J Cell Biochem. 64(2):278-294.

- Makino S, Fukuda K, Miyoshi S, Konishi F and Kodama H, et al. (1999) Cardiomyocytes can be generated from marrow stromal cells in vitro. J Clin Invest. 103(5):697-705.

- Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, Schwartz RE and Keene CD, et al. (2002) Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 418(6893):41-49.

- Avila LM, Becerra A, Avila J. (2008) Biology of stem cells. Med Main News. 2:10-14.

- Avila LM, Gomez C, Becerra A. (2008). Biología de las Células Stem. In: Colombia Los Retos De La Salud Sexual Y Reproductiva En Colombia. Distribuna Editorial Medica. 10-14.

- Garcia BA, Prada MR, Ávila-Portillo LM, Rojas HN and Gómez-Ortega, et al. (2019) New technique for closure of alveolar cleft with umbilical cord stem cells. JCraniof Surg. 30(3), 663-666.

- Hassanein SM. (2004) Human umbilical cord blood CD34-positive cells as predictors of the incidence and short-term outcome of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Cell Transplant. 13(6):729-739.

- Kurtzberg J, Troy JD, Bennett E, Durham R, and Balber AE. (2016) Allogeneic umbilical cord blood infusion for adults with ischemic stroke (CoBIS): Clinical outcomes from a phase 1 safety study. Blood. 128(22):2284.

- Henning RJ, Abu-Ali H, Balis JU, Morgan MB and Willing AE, et al. (2004). Human umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction. Cell Transplant. 13(6):729-739.

- Allewelt HB, Patel S, Prasad VK, Kurtzberg J and Driscoll TA, et al. (2016) Umbilical cord blood transplantation for cartilage hair hypoplasia: A single-center experience demonstrates excellent outcomes using myeloablative preparative regimens. Bio Blood Marrow Transplant. 22(3):235.

- Rajput BS, Chakrabarti SK, Dongare VS, Ramirez CM, Deb KD. (2015) Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Safety and feasibility study in India. J Stem Cells. 10(2):141-156.

- Li P, Cui K, Zhang B, Wang Z and Shen Y, et al. (2015) Transplantation of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stems cells for the treatment of Becker muscular dystrophy in affected pedigree members. Inter J Mol Med. 35(4):1051-1057.

- Bordon V, Gennery AR, Slatter MA, Vandecruys E and Laureys G, et al. (2010) Clinical and immunologic outcome of patients with cartilage hair hypoplasia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 116(1):27-35.

- Langer R, and Vacanti JP. (1993) Tissue engineering. Science. 260(5110):920-926.

- Kaigler D, and Mooney D. (2001) Tissue engineering's impact on dentistry. J Dent Edu. 65(4):456-462.

- Koyano K. (2012) Toward a new era in prosthodontic medicine. J Prosthodont Res. 56(1):1-2.

- Kirkwood KL. (2008) Periodontal diseases and oral bone loss. In: Rosen, C. J. (Ed.), Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism (7th ed., pp. 510-513). Washington, DC: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

- Atwood DA. (1971) Reduction of residual ridges: A major oral disease entity. J Prosthe Dent. 26(3):266-279.

- Egusa H, Sonoyama W, Nishimura M, Atsuta I, and Akiyama K. (2012) Stem cells in dentistry-Part I: Stem cell sources. J Prosthod Res. 56(3):151-165.

- Takahashi K, and Yamanaka S. (2006) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 126(4):663-676.

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M and Ichisaka T, et al. (2007) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 131(5):861-872.

- Horwitz EM, Le Blanc K, Dominici M, Mueller I and Slaper-Cortenbach I, et al. (2005). Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 7(5):393-395.

- Li B, Ouchi T, Cao Y, Zhao Z, and Men Y. (2021) Dental-derived mesenchymal stem cells: State of the art. Frontr Cell Develop Bio. 9:654559.

- Koh KS, Oh TS, Kim H, Chung IW and Lee KW et al. (2012) Clinical application of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells in progressive hemifacial atrophy (Parry-Romberg disease) with microfat grafting techniques using 3-dimensional computed tomography and 3-dimensional camera. Ann Plastic Surg. 69(3):331-337.

- Bueno DF, Kerkis I, Costa AM, Martins MT and Kobayashi GS, et al. (2009) New source of muscle-derived stem cells with potential for alveolar bone reconstruction in cleft lip and/or palate patients. Tissue Eng Part A. 15(2):427-435.

- Mohanty P, Prasad NKK, Sahoo N, Kumar G, Mohanty D, and Sah S. (2015) Reforming craniofacial orthodontics via stem cells. J Inter Soc Prev Commu Dent. 5(1):13-18.

- Baena ARY, Casasco A and Monti M. (2022) Hypes and hopes of stem cell therapies in dentistry: A review. Stem cell Review Rep. 18(4):1294-1308.

- Huang H, Yang R, and Zhou YH. (2018) Mechanobiology of periodontal ligament stem cells in orthodontic tooth movement. Stem Cells Inter. 2018(1):6531216.

- Safari S, Mahdian A and Motamedian SR. (2018) Applications of stem cells in orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics: Current trends and future perspectives. World J Stem Cells. 10(6):66.