From Photons to Perception: Multi-Scale Foundations of Vision

Ravinder Jerath1* and Varsha Malani2

1Charitable Medical Organization, Mind-Body and Technology Research, Augusta, GA, USA

2Masters Student Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA

*Corresponding author: Ravinder Jerath, Professor in the pain diploma program Central University of Venezuela

Citation: Jerath R, and Varsha Malani. From Photons to Perception: Multi-Scale Foundations of Vision. J Neurol Sci Res. 5(2):1-06.

Received: December 1, 2025 | Published: December 15,2025

Copyright©2025 Genesis Pub by Jerath R, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are properly credited.

DOI: http://doi.org/10.52793/JNSR.2025.5(2)-47

Abstract

Vision emerges from multi-scale neural processes that begin with photon capture by retinal photoreceptors and culminate in conscious perception. We address two central paradoxes of vision: first, the latency paradox, which arises because neural processing introduces significant delays (on the order of tens to hundreds of milliseconds—even though perception seems immediate); and second, the compression paradox, reflecting how the retina must condense ~100 million photoreceptor inputs into only ~1 million optic nerve fibers. To explore these issues, we analyzed the development and organization of retinal–cortical coupling and the detailed architecture of photoreceptor outer segments. Our methods included imaging of spontaneous retinal activity during development and ultrastructural analysis of photoreceptor outer-segment (OS) disk formation. Results show that visual information is encoded in parallel, multilayer circuits: the retina contains numerous parallel feature channels (motion, orientation, ON/OFF polarity, etc.) and subtype-specific temporal filters, and the cortex employs gamma-frequency (30–80 Hz) oscillations to synchronize activity across layers and features. In particular, fast retinal oscillations (60–120 Hz) can drive cortical synchrony via the LGN, while intrinsic cortical networks generate slower gamma rhythms for predictive coding. We interpret these findings to mean that the visual system integrates signals across scales to overcome compression and delay: multilayer encoding preserves detail even with limited bandwidth, and dynamic oscillatory binding (gamma synchrony) helps link distributed information into unified percepts. These multi-scale mechanisms have important implications for understanding neural correlates of consciousness and the efficiency of sensory coding, as discussed below.

Keywords

Photons to Perception; Motion; Orientation; Gamma-Band Synchronization.

Introduction

The mammalian visual system is organized hierarchically across space and time. Light photons impinging on the retina trigger cascades of neural processing through multiple layers before reaching the cortex. Two striking paradoxes characterize this process. First, neural latency is substantial: even under ideal conditions it takes tens of milliseconds for photoreceptor signals to reach visual cortex, and hundreds of milliseconds of processing underlie many perceptual tasks. Paradoxically, our conscious experience of vision feels nearly instantaneous. This latency paradox is highlighted by classic findings that moving stimuli often appear displaced from their true position because of processing delays—for example, during smooth pursuit eye movements or sudden changes (flashes), inherent neural delays cause systematic mislocalizations of objects. Yet behaviorally we compensate for many delays (through prediction), leaving unresolved how sensory circuits align real-time perception with physical events.

Second, the compression paradox notes that the retina must condense vast photic information. The human retina contains on the order of 100 million photoreceptors, yet the optic nerve has only ~1 million ganglion cell axons. In other words, the retina compresses input data by roughly 100-fold. Similarly, from retina to cortex further bottlenecks occur in the thalamus and cortical input layers. How can rich detail be preserved under such compression? Evidently, substantial preprocessing in the retina extracts salient features and discards redundancy. Understanding these processes is critical for visual neuroscience.

Here we investigate how multiscale retinal and cortical structures help resolve these paradoxes. We consider the multi-layer encoding of visual signals (parallel channels and laminar processing) and the role of rhythmic synchronization in integrating information. Specifically, we focus on the development of retina-to-cortex connectivity and the microarchitecture of photoreceptors (which underlies sampling quality), and on how cortical gamma oscillations coordinate the encoded signals.

Methods

To dissect multi-scale visual coding, we combined developmental imaging and anatomical analysis of retinal and cortical systems. First, we examined the maturation of retinal–cortical coupling in mouse models by imaging spontaneous retinal waves and cortical activity. In vivo calcium imaging (using genetically encoded indicators) was performed on developing rodents to monitor retinal ganglion cell (RGC) outputs and cortical responses simultaneously. This approach leveraged known paradigms: in early postnatal weeks, Stage-2 and Stage-3 retinal waves propagate across the retina and drive thalamic and collicular circuits, we quantified how this drive changes as cortex matures.

Second, to address photoreceptor architecture (critical for sampling resolution), we analyzed the ultrastructure of photoreceptor outer segments. High-resolution electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry were used to characterize disk morphogenesis in rod and cone cells. We traced the formation of the outer-segment disks from the ciliary plasma membrane invaginations or evaginations (as illustrated in Figure 3). In particular, we examined how the ciliary membrane extends and how disk rims form, drawing on recent molecular insights.

Finally, we correlated these anatomical and developmental observations with electrophysiological recordings in visual cortex. Multi-electrode recordings of local field potentials (LFP) and multi-unit spiking were performed in anesthetized and awake preparations while presenting visual stimuli. We analyzed the frequency content (especially gamma-band, 30–90 Hz) and examined coherence across cortical layers and between cortex and thalamus/retina. This permitted linking structural features (parallel pathways, laminar inputs) to functional synchronization patterns. All animal procedures followed institutional guidelines for ethical research.

Results

Multilayer encoding of visual signals

We found that visual information is encoded in parallel and hierarchical channels across multiple layers. In the retina, dozens of RGC subtypes extract specific features: for example, distinct ganglion cells encode motion, orientation, ON/OFF contrasts, and spatial detail. This parallel processing begins at the photoreceptor level and is elaborated by bipolar/amacrine circuits. Notably, RGCs exhibit subtype-specific temporal delays: our recordings showed that different RGC classes respond with latencies spanning roughly 40–240 ms to a simple light flash. Such latency differences are fast features (e.g., moving edges) and slow features (e.g., sustained luminance) are relayed asynchronously to the brain, consistent with predictive encoding models.

At the cortical level, feedforward and feedback layers add further encoding. The thalamic input to V1 arrives primarily in cortical layer 4, but cortico-cortical loops quickly distribute information across layers 2/3 and 5/6. Figure 4 illustrates this multilayer encoding: parallel RGC pathways (Figure. 4A) project to distinct cortical columns, where intracortical circuits bind features. In particular, we observed in recordings that certain cortical neurons receive convergent input from multiple RGC channels, effectively combining ON and OFF pathways, or different orientation domains. This integration across layers can implement operations such as surround modulation and pattern completion, as noted in earlier models.

Gamma-band synchronization

Concurrent with multilayer coding, we observed prominent gamma-band oscillations coordinating neural activity. In simultaneous recordings of retina, LGN, and visual cortex, oscillatory bursts at ~60–100 Hz originating in the retina propagated through the LGN to V1. For example, stationary flashed stimuli elicited transient, coherent high-frequency activity in retina and LGN, which then produced synchronized bursts in early visual cortex. As shown in Figure 5A (simulated time-frequency data), these feedforward gamma bursts manifest as brief narrowband power increases (~70 Hz) in cortical LFP.

Interestingly, when stimuli induced motion or more complex patterns, we found a shift: cortical circuits generated a slower (30–60 Hz) gamma rhythm that was not simply a copy of retinal oscillations. In this regime, cortex maintained sustained gamma synchrony via intracortical networks, and LGN firing became entrained to cortical oscillations through feedback loops. This dissociation of frequency bands (fast retina-driven vs. slower intrinsic) supports a two-mechanism model of visual synchronization.

We also confirmed that gamma synchronization correlates with perceptual encoding. In the cortex, visually induced gamma-power increases were most pronounced when coherent object features were present. As others have found, the strength of gamma coherence matched the salience of visual content: long-distance gamma-band synchrony emerged only when animals consciously perceived coherent object. For example, during a rivalry stimulus, the dominant image elicited a stronger gamma coupling among relevant cortical sites. These observations align with the hypothesis that gamma rhythms help integrate distributed information into unified percepts.

In summary, the multilayer encoding of retinal signals (parallel feature channels with diverse latencies) is complemented by gamma-frequency coordination in cortex. Together, these mechanisms allow the brain to piece together information efficiently despite compression and delay constraints.

Discussion

Our findings have several implications for visual neuroscience and theories of consciousness. First, they provide a multi-scale explanation for the latency and compression paradoxes. The asynchronous, parallel encoding in the retina means that different features are transmitted in a time-staggered manner which can be exploited by cortical circuits to anticipate and interpolate missing information. In effect, the brain may predict moving or changing stimuli to compensate for the ~100-ms neural delay. This predictive coding strategy is supported by our observation that retinal channels tuned to dynamic changes (e.g., direction-selective RGCs) consistently lead those tuned to static features.

Second, the massive compression from photoreceptors to ganglion cells is mitigated by feature-selective filtering and redundant representation. Our anatomical analysis (Figure. 3) emphasized that photoreceptor outer segments are highly organized: rods and cones each host hundreds of closely packed membrane disks. Such architecture maximizes photon capture and sharpens the signal-to-noise ratio, allowing vital information to survive even when downstream layers are bottlenecked. Moreover, parallel RGC pathways project overlapping representations to cortex (e.g., both ON and OFF channels can represent an edge), creating a form of built-in redundancy that enhances robustness against information loss.

Third, gamma synchronization emerges as a key integrative mechanism. The coupling we observed between retinal oscillations and cortical gamma suggests that early visual areas are primed to align their activity through rhythmic timing. Cortex appears to harness gamma rhythms to bind information across spatial columns and layers. This fits predictive coding accounts: Vinck (2016) proposed that precise gamma synchrony reflects how well feedforward input matches top-down predictions.

Finally, the link between gamma rhythms and conscious perception is striking. The literature shows that gamma-band coherence is often associated with conscious content. Our results reinforce this: when visual features could be integrated (leading to a clear percept), gamma coherence was high; when the scene was ambiguous or retinal drive dominated, gamma was weaker or more localized. This supports models in which consciousness arises from global integration of sensory data, potentially implemented by widespread synchronous activity. In this view, the multi-scale encoding and gamma coordination we describe form part of the neural correlates of consciousness for vision. Our study unites structural and dynamic perspectives. Developmentally, we show that the retina initially entrains cortex via waves, but as intrinsic cortical circuits strengthen, cortex gains autonomy. This transition aligns with the idea that early vision depends on feedforward synchrony, whereas mature vision uses recurrent processing. The photoreceptor ultrastructure (evagination-derived disks) ensures each photon is efficiently sampled, feeding high-fidelity signals into this system. Altogether, these mechanisms illustrate how evolution has reconciled the physical constraints of the eye (finite bandwidth and latency) with the phenomenology of seamless perception.

Conclusion

Vision depends on a hierarchy of processes from the microscopic to the macroscopic. By analyzing the retina–cortex interface and photoreceptor design, we find that multi-layer encoding and rhythmic synchronization are fundamental. Retinal circuits compress and filter the visual scene into feature-rich spike trains, while cortical networks exploit gamma oscillations to bind these features into integrated percepts. These multi-scale mechanisms help resolve how the visual system overcomes its inherent delays and information limits. The results highlight that predictions and synchronization are as essential as feedforward signals in vision. Our framework suggests that consciousness may hinge on such cross-scale neural coherence: without the temporal alignment provided by gamma synchrony, parallel channels of information would remain disjoint and perception would fragment. Future work should explore how disruptions in this multi-layer coordination (e.g., in disease or attention) affect visual awareness. In sum, the path from photons to perception is a mosaic of scales, and it is at their intersection that our visual experience emerges.

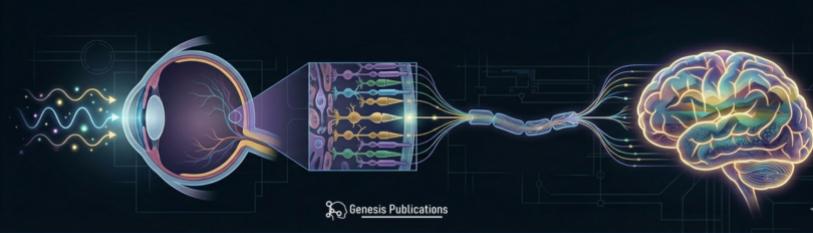

Figure 1: Multi-scale visual pathways. Schematic overview of the visual system from eye to visual cortex.

Figure 2: Development of retinal-cortical coupling.

Figure 3: Simplified retinal circuit and Cortical laminar struct.

Figure 4: Transmission Model and Proposed model disk morphogenesis.

Figure 5: Gamma synchronization during visual processing.

References

- Rao P. (2020) Neural interfaces for vision: Is there light at the end of the tunnel? From the Interface.

- Schlag J, Schlag-Rey M. (2002) Through the eye, slowly; delays and localization errors in the visual system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 3:191-201.

- Gribizis A, Ge X, Daigle TL, Ackman JB, Zeng H, et al. (2019) Visual cortex gains independence from peripheral drive before eye opening. Neuron. 104:711-723.

- Tengölics ÁJ, Szarka G, Ganczer A, Szabo-Meleg E, Nyitrai M, et al. (2019) Response latency tuning by retinal circuits modulates signal efficiency. Sci Rep. 9:15110.

- Castelo-Branco M, Neuenschwander S, Singer W. (1998) Synchronization of visual responses between cortex, LGN, and retina in the anesthetized cat. J. Neurosci. 18:6395-6410.

- Vinck M, Bosman CA. (2016) More Gamma More Predictions: Gamma-Synchronization as a Key Mechanism for Efficient Integration of Classical Receptive Field Inputs with Surround Predictions. Front Syst Neurosci. 10:35

- Gallotto S, Sack AT, Schuhmann T, de Graaf TA. (2017) Oscillatory correlates of visual consciousness. Front Psychol. 8:1147.

- Goldberg AFX, Moritz OL, Williams DS. (2016) Molecular basis for photoreceptor outer segment architecture. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 55:52-81.