Molecular Pathways and Statistical Analysis of Alzheimer’s Disease

KS Ravi Teja1, Sai Lakshmi Gundimeda2, Jahnavi Susrutha Meduri2, Anushree Ramprasad2, Ashwini R3, Shaik Shafi3, R Kowshik Aravalli4, Srihitha Kante5 and A Ranganadha Reddy6*

1Clinical Data Specialist IQVIA Hyderabad

2Research Assistant ICMR-NARFBR, Hyderabad India

2 Executive of QC, QA & Regulatory, Relisys Medical Devices Pvt Ltd, Hyderabad India

2Database Coordinator, LabCorp Bengaluru Karnataka India

3Pharmacovigilence Service Associate, Accenture Bengaluru Karnataka

3Clinical Data Specialist IQVIA Hyderabad

4Assistant Professor, Department of Biotechnology, Amity University Bengaluru Karnataka

5Associate Data team lead, IQVIA Hyderabad

6Professor, Department of Bioinformatics, Vignan Foundation for Science Technology and Research Vadlamudi Guntur (dt).

*Corresponding author: A. Ranganadha Reddy, Professor, Department of Bioinformatics, Vignan Foundation for Science Technology and Research Vadlamudi Guntur (dt).

Citation: Teja KSR, Gundimeda SL, Meduri JS, Ramprasad A, Ashwini R, et al. Molecular Pathways and Statistical Analysis of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Neurol Sci Res. 6(1):1-35.

Received: January 10, 2026 | Published: February 02, 2026

Copyright© 2026 by Teja KSR, et al. All rights reserved. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: http://doi.org/10.52793/JNSR.2026.6(1)-55

Abstract

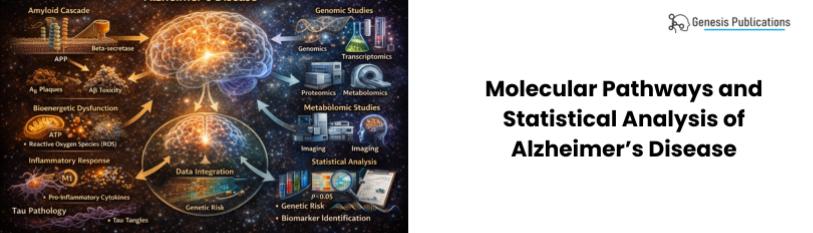

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is dementia of memory and other brain cell functions like thinking, personality, and others. More oxidative stress and misfolded proteins cause it. As nerve cells, connections, and molecular pathways important to this study are slowly lost in different tissues, the brain shrinks. Wnt signaling, AMPK, mTOR, Sirt1, and peroxide proliferator-activated receptors are examples. This is the latest way to slow or stop Alzheimer's disease. This study examines healthy brain cells from an AD patient using microarrays. After uploading these samples to a DNA spot, they will undergo cell culture, RNA isolation, reverse transcription (cDNA), and fluorescent dye addition to differentiate the cells. To graph colored dyes, we will combine cDNA probes from oligonucleotide microarray sequences from both samples. This method shows that A.D. cells grow faster than normal cells. Normalizing data and getting feature counts from de-Seq and statistical analysis require NGS studies. Meanwhile, we're studying how drugs interact with proteins to determine how Alzheimer's disease treatments affect patients. Donepezil may slow Alzheimer's progression or cause strange body changes, so it's important to know. How the drug interacts with non-Alzheimer's protein drugs is also crucial. Since aducanumab is an injection, we will study its efficacy and side effects in sick people.

Keywords

Molecular Pathways; Statistical Analysis; Alzheimer’s Disease.

Aim & Objective

Aim of this study is to observe the gene expression levels from different cells of Alzheimer’s genes with different statistical tests and methodologies, metabolic pathways also with, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Alzheimer’s drugs.

Introduction

Cholinergic neuron degeneration is the primary cause of Alzheimer's disease (AD), a neurodegenerative condition [1]. This can affect behavior, motor skills, and cognition. It causes dementia in 10% of 65-year-olds and 50% of 85-year-olds [2]. It's the leading cause of dementia in seniors. Around 4 million Americans have Alzheimer's. The WHO estimates that 114 million more people will have Alzheimer's by 2050 [19]. This will strain the economy and minds. There is no drug on the market that can slow or stop Alzheimer's brain cell death. Researchers found that sick people's brains have low glucose levels, indicating illness. Slowing basal glucose metabolism in AD will be a sensitive sign that could be used to track the disease's progression [3]. Alzheimer's disease may worsen due to extracellular amyloid beta (AB) plaque adhesion. Sleep deprivation can cause this. Most Alzheimer's disease damage is to the hippocampus and thalamus. More evidence links genetic and environmental factors to Alzheimer's disease [4].

Exploring diverse pathways and biomarkers in alzheimer's disease

A small number of molecular pathways are involved in Alzheimer's disease. The provided abstract discusses the topics of Wnt signaling [5], 5' adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), Sirtuin 1 (Sirt1) [6], and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor coactivator 1.

Bmp4 overexpression for app/tau upregulation and alzheimer's memory deficits

There was a study that looked at how higher levels of BMP4, APP, and Tau were linked to memory loss in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease (AD) [7,8]. The findings showed that giving AD mice too much BMP4 increased the levels of APP and Tau, made A-plaque buildup worse, and caused memory and recognition problems [9]. This means that BMP4 might be a key part of how AD works and could be a good target for treatment to improve memory [10].

The CB2 cannabinoid receptor and its potential activity against Alzheimer's disease

According to research, Alzheimer's disease (AD) may be treated by focusing on the CB2 cannabinoid receptor, which is a component of the endocannabinoid system [11]. Neurons contain CB2 receptors, especially in regions like the cortex and hippocampus where AD pathology is prevalent [12]. CB2 receptor activation can clear Aβ plaques, lessen neuronal damage, and lower pro-inflammatory cytokines. This shows that activating CB2 receptors may be a useful therapeutic approach for AD [13]. To ascertain its efficacy, safety, and mechanisms, more research is required.

Corpus callosum shape and size changes in early alzheimer's disease: a longitudinal mri study using the oasis brain database

There are big differences in the corpus callosum's size and shape between people with AD and healthy controls in an MRI study that looked at changes in the corpus callosum in early-stage AD over a long period of time [14]. The OASIS Brain Database, which contains MRI scans and clinical information from individuals with various cognitive impairments, provided the data for the study [15]. With smaller areas, volumes, and thicknesses, the results imply that neurodegenerative processes are still present in the early AD group [16]. Additionally, correlational studies found links between cognitive decline and changes in the corpus callosum [17]. This suggests that these changes may be related to the cognitive problems caused by AD.

APP (Amyloid beta precursor protein)

The APP gene is extremely conserved and has 18 exons (290 kilobases) [18]. Depending on the length of the amino acids, it undergoes alternative splicing, resulting in 695-770 amino acids that resemble beads on a string. The APP gene is found on chromosome 19 21q21.3. APP695, APP714, APP751, APP770, and other isoforms will result from this splicing, with APP695 being predominantly expressed in the central nervous system. In both the peripheral and central nervous systems, APP751 and APP770 are expressed.

In AD brain, there was a considerable rise in the ratios of APP770 mRNA and APP770-plus-APP751 mRNAs. The Kunitz protease inhibitor (KPI) domain is present in both APP751 and APP770, and APP770 additionally has an OX-2 domain. Conversely, APP695 is devoid of both of these domains. According to reports, the brains of AD patients have higher levels of the KPI-containing APP isoforms, which may be linked to the disease's advancement. Aside from the KPI domain's activity as a protease inhibitor, no additional clear functional distinctions between the various APP isoforms have been discovered (APP563) [3]. The amyloid sequence is coded for in part by exons 16 and 17.

App The overexpression of Rho-GTPase, Bcl-2, and NF-κB signaling pathways in neuronal cells has been observed to impact synaptic plasticity and neuronal survival in Alzheimer's disease (AD). Proteases are a class of enzymes that cut APP after it is generated by neurons’ is proteolytically cleaved by α-, β-, and γ-secretases via at least two primary pathways (the non-amyloidogenic and amyloidogenic pathways [20].

The non-amyloidogenic pathway

APP is cleaved by α-secretase in the non-amyloidogenic process, yielding two fragments: the 83 amino acid C-terminal fragment (C83) [21], which stays in the membrane, and the N-terminal ectodomain (sAPPα), which is released into the extracellular medium [22]. ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM171 are the three enzymes that have been found to exhibit α-secretase activity. Most importantly, APP is cleaved by α-secretase within the Aβ domain to stop the synthesis of Aβ peptide [23]. The C83 membrane fragment is noteworthy because it can be cleaved by γ-secretase to provide the APP intracellular domain (AICD) and a brief segment known as P3 peptide [24].

The amyloidogenic pathway

The formation of neurotoxic Aβ is a result of the amyloidogenic pathway. The initial proteolysis phase, which releases a large N-terminal ectodomain (sAPPβ) into the extracellular medium, is mediated by β-secretase (BACE1) [25]. The membrane still contains a 99-amino acid C terminal segment (C99). The first amino acid of Aβ is correlated with the recently revealed C99 N-terminus [26]. The Aβ peptide is released upon successive cleavage of this segment by γ-secretase, specifically between residues 38 and 43. Presenilin 1 or 2 (PS1 and PS2), nicastrin, anterior pharynx defective (APH-1), and presenilin enhancer 2 (PEN2) 6–42 make up the complex of enzymes known as γ-secretase [27]. This form is thought to be more neurotoxic due to the additional two amino acids, which increase the likelihood of misfolding and subsequent aggregation. Alzheimer's disease and elevated plasma levels of Aβ1-42 have been linked [28].

Function of APP in the central nervous system

Figure1: Function of APP in the central nervous system [29].

ApoE

- ApoE =299 amino acid glycoprotein

- Molecular weight =34 KDa

The liver's hepatocytes and macrophages produce ApoE, it’s a lipid transporter that distributes phospholipids and, choroid plexus cells cholesterol throughout the body. ApoE highly expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) by astrocytes, activated microglia, vascular mural cells, and to a lesser amount in stressed neurons, apoE is unable to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [30]. Human apoE is found in three primary isoforms, which are identified by differences in amino acid positions 112 and 158 between arginine and cystine (apoE2: Cys112/Cys158; apoE3: Cys112/Arg158; apoE4: Arg112/Arg158) [31]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis of mutated monomeric apoE3 revealed substitution between single amino acids between apoE4 and apoE3, and between apoE3 and apoE2. This significantly changes the functionality of apoE, leading to isoform-specific structural variations that affect stability, lipid binding, receptor binding, and oligomerization propensity [32].

The apolipoprotein E (Apo-E) protein is produced by the gene known as apolipoprotein (APOE). This protein works with the body's lipids to create lipoproteins, which are responsible for encasing and transferring fats and cholesterol through the bloodstream [33]. The metabolism of lipids in animal bodies is influenced by this process. A protein that binds to liver and peripheral cell receptors and helps break down lipoprotein components rich in triglycerides is encoded by the APOE gene. The pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease is associated with Apo-E because of its pivotal function in lipid metabolism [34]. When issues arise, the APOE gene is more likely to develop Alzheimer's disease because it is involved in producing a protein that aids in the bloodstream's transportation of cholesterol and other forms of fat (National Institute of Aging). More precisely, it has been established that the APOE E4 allele raises the risk of late-onset Alzheimer's disease structure of the APOE.

The structure of the APOE gene provides further explanation to its linkage to Alzheimer’s disease. The APOE gene is located on chromosome 19, at position q13.32. It contains three main regions: (1) N terminal region, which contains the receptor binding site and four helices, (2) C terminal region containing the lipid binding site and three helices, and (3) intervening hinge region that links the N and C terminal regions. The APOE isoforms differ with a unique amino acid combination in these positions, and the amino acid differences among the isoforms significantly affect their structures, thus their roles in the disease. Studies found that APOE E2 is severely defective in the LDL receptor binding due to its structural difference, altering the receptor binding region and aiding the mechanism of type III hyperlipoproteinemia [35].

Like a common saying in science, that the structure equals function, understanding the structure of the APOE gene unraveled its significance to cardiovascular, neurological, and infectious diseases. The APOE gene was discovered in 1993 by the Duke Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center group. While the team was investigating two diverse experimental streams, they were able to find a genetic linkage of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease located at chromosome 19q13 [36]. Following this discovery, a consistent protein impurity was found from a series of amyloid-beta binding studies, in the form of gel separation analyses (2006). It was then recognized that APOE isoforms are associated with differing ages of onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

The APOE gene is located on chromosome 19, with its exact coordinates of 44,905,796-44,909,393. It is 3598 bp long, with a chromosomal position of q13.32, and it contains six exons. There are three splice forms described and it contains five transcripts. The two closest neighbors of the APOE gene are: TOMM40 and APOC1. The CpG island is located at Chr 19:44908464 - 44909343, with a count of 90, and another one at Chr 19: 44890577-44891735. The gene does not share its promoter region with another gene, and there is DNase-I

Hypersensitivity (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374288795_BIO_315-_Genetics-_APOE_Gene_Report).

Presenilin 1 (PSEN1)

PSEN1 present on chromosome 14q24.2. The 467 amino acid protein it encodes is made up of 12 exons and has 9 C-terminal transmembrane domains that are located in the lumen/extracellular space [37]. Full-length PSEN1 is an inactive precursor that can undergo endoproteolytic cleavage within hydrophobic domain 7 in a wide cytosolic loop to create a heterodimer made up of a 20 kDa C-terminal fragment (CTF) and a 30 kDa N-terminal fragment (NTF) [38]. The majority of PSEN1 forms seen in cells and its active forms are NTF/CTF heterodimers; full-length proteins that are not intended for the cleavage pathway are broken down rapdly. PSEN1 endoproteolysis could be a crucial phase in the activation of the γ-secretase complex. Moreover, the γ-secretase complex's catalytic core could be formed by NTF/CTF heterodimers. The two catalytic aspartate residues in PSEN1 (Asp257 at NTF and Asp385 at CTF) are critical for the activity of γ-secretase. Every mutation that affects one of the two conserved aspartates can eliminate the activity of γ-secretase [39].

After APP processes α-and β-secretases, PSEN1 is implicated in the C-terminal transmembrane region of APP and the γ-secretase-produced amyloid-β peptide (Aβ42) [40]. PSEN1, a critical regulator protein in γ-secretase cleavage, may not be an enzyme in and of itself [16]. The transfer of the C-terminal APP fragment to the gamma secretase complex may also involve PSEN1. Amyloid peptide synthesis may be changed as a result of impaired APP processing caused by a deficit in PSEN1 function [41]. Protein activities may depend on a number of presenilin domains [24]. Nct protein interacts with the C-terminal segment. Furthermore, it has the ability to regulate the activity of γ-secretase by binding ATP through its nucleotide binding site. Moreover, the C-terminal segment attaches to APP and engages in interaction with TM1.

PSEN1's N-terminal region (TM1, HL1, and TM2) is essential for catalyzing the γ-secretase complex's substrates [37]. These domains may also affect the coordination of substrate docking to the enzyme and PSEN1 endo-proteolysis. The interaction between TM2 and TM3 may affect the conformation of γ-secretase, making it either "fully open" or "semi-open," and it may also regulate the active site's accessibility. While mutations may cause the enzyme to adopt a "open" conformation and produce longer amyloid peptides, the "semi-open" conformation of the enzyme may be optimal for the synthesis of short amyloid [42].

Figure 2: Function of PSEN1 in the central nervous system.

Presenilin 2 (PSEN2)

Another gene encoding the transmembrane protein PSEN2 revealed a strong correlation with AD less than a year after PSEN1 was mapped. PSEN2 and PSEN1 are almost 60% similar, and PSEN2 is found on the long arm of chromosome 1 (1q42.13). It is projected to have nine transmembrane domains and a large cytoplasmic loop domain between the sixth and seventh domains [43]. It is composed of 12 exons that encode a 448-amino-acid protein (atlasgeneticsoncology.org). The PSEN2 isoforms are two. The placenta, skeletal muscle, and heart contain isoform 1, whereas the brain, heart, placenta, liver, skeletal muscle, and kidney include isoform 2, which is devoid of amino acids 263–296 [44]. The γ-secretase complex's catalytic activity is provided by PSEN2, one of the four necessary proteins in the complex. PSEN2 is assumed to be PSEN1's compensatory partner Unlike PSEN1 which is extensively distributed, PSEN2 is known to be mostly localized to a specific subcellular compartment, such as late endosomes and lysosomes The intracellular Aβ peptide pool was previously associated with an early AD event; PSEN2's more restricted localization adds to it [45].

Figure 3: Function of PSEN2 in the central nervous system.

ADAM Metallopeptidase Domain 10

The protein ADAM10 aids in the signaling, retinal pigmentation, and Notch2 activation associated with Alzheimer's disease. It needs ADAM17 and is involved in protein homodimerization and signaling receptor binding. ADAM proteins, which contain binding and protease domains, hydrolyze TNF-alpha and E-cadherin. Transcripts for related processed proteins are created through alternative splicing. By cleaving membrane-bound precursors, ADAM10 releases soluble TNF-alpha, proteolyzes liquid JAM3, APP, heparin-binding epidermal growth factor, CD44, CDH2, and ephrin-A2, and stops neurogenesis suppression. It removes ITM2B, CORIN, and other proteins, forms the transmembrane, and releases the FasL ectodomain.

FN1

fn1b, the ortholog of human FN1, was mutated to cause loss-of-function (LOF) in zebrafish models. Findings indicate that pathological FN1 accumulation can hinder harmful protein function by reducing gliosis, improving gliovascular re-modeling, and amplifying the microglial response. Research indicates that LOF variations in FN1 may lower APOEε4-related AD risk, and that vascular deposition of FN1 is associated with the pathogenicity of APOEε4. These findings offer new insights into possible therapeutic treatments that target the ECM to reduce AD risk [46].

The role of pharmacology and cholinesterase inhibitors

The term "pharmacology" describes a drug's capacity to interact with several targets in the human body and produce a range of therapeutic outcomes [47]. One popular class of medications used to treat Alzheimer's disease is cholinesterase inhibitors [48]. These inhibitors work by raising acetylcholine levels in the brain and enhancing cholinergic neurotransmission, which inhibits enzymes such as butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) and acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [49,50]. Additionally, they lessen neuroinflammation and regulate the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, both of which are believed to hasten the onset of Alzheimer's disease [51]. In addition to strengthening cells, reducing oxidative stress, and extending neuronal survival, cholinesterase inhibitors may also slow down the neurodegenerative progression of Alzheimer's disease [52].

Cholinesterase inhibitors can change the brain's capacity for making new connections, known as synaptic plasticity, which is advantageous for memory and learning [53]. It is common for them to be taken with other drugs, like memantine, to treat neuroinflammation, glutamate excitotoxicity, and cholinergic deficiencies, which are all parts of how the disease works [54]. These polypharmacological treatments may have more advantageous synergistic effects than individual targeting.

Cholinesterase inhibitors are very important in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease because they work on the cholinergic system and connect with other receptors and pathways [55]. They protect neurons, enhance cholinergic neurotransmission, reduce inflammation, and modify the way connections evolve [56]. By comprehending and applying these multi-pharmacological effects, Alzheimer's disease treatment plans can be improved, and new treatments can be created [57].

Drugs used to treat Alzheimer’s

- Cholinergic Activators: Tacrine, Rivastigmine, Donepezil, and Galantamine

- Glutamate (NMDA): memantine

- Miscellaneous: Piracetam, Pyritinol, Piribedil, and Ginkgo biloba

The brain, spinal cord, autonomic nervous system (ANS), sympathetic motor neurons, sensory neurons, primary sensory neurons, and primary sensory neurons are all parts of the nervous system [58]. Cholinergic activators are neurotransmitters that are centrally active. [59]. They are also referred to as anticholinesterases or para-sympathometics. In the human body, these are classified into two types and are centrally active.

- Acetylcholinesterase (AchE)

- Butyrylcholinesterase (BuchE)

AchE is a compound that is present in glial cell synapses and is created when acetic acid reacts with choline. Acetylcholine is compounded. BuchE is found in the plasma of humans. These hydrolyze blood drug molecules and dietary esters. BuchE resembles AchE [60].

Carbamides, organophosphates, rivastigmine, tacrine, Pyflos, donepezil, galantamine, physostigmine, neostigmine, and pyridostigmine are some of the anti-cholinesterases that can be reversed or irreversible [61].

Rivastigmine

- Pharmacodynamics: It is a carbamate derivative and inhibits AchE and BuchE

- Pharmacokinetics: It is highly lipid soluble or fat soluble and enters brain easily

- DOA (Drug of Action): 8hrs

- Side effects: Abdominal pain, Nausea, Vomiting, Diarrhea, Hepatotoxicity

- Uses: Used to treat Alzheimer’s disease

Donepezil

- Pharmacodynamics: Effects both AchE and BuchE

- Pharmacokinetics: Not highly lipid soluble when compared with Rivastigmine.

- DOA (Drug of Action): 24hrs

- Side effects: Abdominal pain, Nausea, Vomiting, Diarrhea, Hepatotoxicity etc.,

Glutamine

- It is a Natural Alkaloid, which selectively inhibits cerebral AchE & has some direct action on Nicotinic Receptors.

- DOA: 8hrs

- Side effects: Abdominal pain, Nausea, Vomiting, Diarrhea, Hepatotoxicity

Aducanumab

- It is a monoclonal IgG1 antibody that inhibits to β-amyloid plagues in the brain.

- Pharmacokinetics: Metabolized into smaller oligopeptides and amino acids

- DOB: 3hrs

- Side effects: Headache, Confusion, Dizziness, Vision abnormality, Nausea, Delirium

Materials and Methods

All the data are taken from publicly available resources (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Using that data we have done gene expression analysis using web-based tool called GenomicScape. Top-ranked genes' levels of expression across multiple sample groups can be created and exported as a heat map. Without assuming anything, the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) tool allows one to determine how samples can cluster together using metric correlations (unsupervised clustering). The samples are displayed along the first two or three principal components, and the PCA tool offers both 2D and 3D views. Tables and figures can be exported, and sample colors are assigned by default or can be selected by the user. We have used (version 5.1) genomic scape software for this analysis. We have done statistical analysis using R program analysis of BioConductor of GCRMA package.

The GCRMA algorithm was used to standardize the publicly accessible data of these eight B cells to plasma cell populations (38 samples) [62].

Results

Alzheimer’s KEGG pathway

Figure 4: The Red colour indicates genes are highly expressed genes in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

WNT signaling pathway

Figure 5: WNT Signaling Pathway.

MTOR signaling pathway

Figure 6: mTOR signaling pathway.

Heatmaps_Student_T test

Different types of naïve B cells (NBCs), centroblasts (CBs), centrocytes (CCs), memory B cells (MBCs), pre-plasma blasts (PrePBs), plasmablasts (PBs), early plasma cells (EPCs), and mature plasma cells (BMPCs) all speak different sets of genes. The data are the SAM multiclass expression contrast of each gene in a given cell subpopulation compared to the others.

T Test: is a statistical test used to compare means of two groups.

Human B cells to plasma cells GCRMA (38 samples)

- Dataset: Human B cells to plasma cells (GCRMA)

- Species: Homo sapiens

- Tissue/Celltype: Blymphopoiesis

- Study type: Gene expression by array

- Platform: Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array

- Normalization: GCRMA

(See figure 7 to 51 in PDF)

Aducanumab

|

Chemical and physical data |

|

|

Formula |

C6472H10028N1740O2014S46 |

|

Molar mass |

145912.34 g·mol−1 |

|

Monoclonal antibody |

|

|

Type |

Whole antibody |

|

Source |

Source |

|

Target |

Amyloid beta |

Table 1: Chemical and physical characteristics of Aducanumab.

Aducanumab is a human IgG1 anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody that the US FDA has approved for the treatment of mild dementia or Alzheimer's disease. It was created by neuroimmune and activates human B-cell clones through an antibody-based therapeutic strategy [63]. The FDA sped up the approval process for Aduhelm because clinical studies with 3482 patients showed a significant decrease in Aβ-amyloid plaque living in 3482 patients [64]. The treatment is the first of its kind that the US FDA has authorized.

Pharmacokinetics

The medication Aducanumab, which is used to treat Alzheimer's disease, was subjected to a population pharmacokinetic study [65]. The research examined concentration data from 2961 patients who were administered the medication either once or more. According to the analysis, the mean concentrations of Aducanumab at different doses peaked within 30 minutes of a 2-hour infusion [66]. The drug's maximum concentration (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC) both rose in direct proportion to the dosage. There was a range of 2.5 to 3.3 hours for the median time to reach Cmax [67]. The volume of distribution (Vd) of aducanumab in steady state was found to be 9.63 L. It's anticipated that the drug will break down [68].

Pharmacodynamics

The medicine aducamumab sticks to fibrils and tells microglial cells to get rid of them. To be effective, however, the drug must cross the blood-brain barrier and consistently destroy amyloid aggregates. Due to the drug's long half-life, it takes about 5 months to achieve its maximum clinical benefit. The length of time needed to remove amyloid plaques, an individual's amyloid burden, their APOE 4 genotype, their age, and the severity of their disease are just a few variables that can affect the lag period. In the Emerge trial, the high-dose group showed the most significant reduction in cognitive decline, possibly because more patients in this group achieved.

Adverse drug actions

- ARIA-E edema of the brain (35% of patients treated with Aduhelm vs. 3% of patients treated with placebo): Headache, altered mental status, disorientation, nausea, vomiting, tremor, and abnormalities in gait are possible symptoms.

- "Headache" (21 % vs. 16%), which encompasses occipital neuralgia, migraine, migraine with aura, and headache.

- ARIA-H microhemorrhage or brain bleeding (19% vs. 7%): Headache, weakness in one side, vomiting, convulsions, reduced consciousness, and stiff neck are some of the symptoms.

- Hemosiderin-related ARIA-H superficial siderosis (15% vs. 2%).

- October (15% vs. 12%)

- Stool (9% vs. 7%).

- Disorientation, delirium, altered mental status, and confusion (8% vs. 4%).

Amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles build up in the brain to cause Alzheimer's disease, a progressive neurodegenerative condition. By decreasing Aβ plaques in the brain and delaying its progression, the novel treatment aducanumab is the first to address this important pathology. The pharmacokinetics of it are good [69].

Lecanemab

Lecanemab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to and targets soluble protofibrils. These are a type of protein that is thought to play a role in the development and progression of Alzheimer's disease [70]. Lecanemab binds to these protofibrils in an attempt to stop their aggregation and lessen the development of amyloid plaques [71]. This might lessen the rate at which the disease progresses and protects neuronal function. Lecanemab may help people with early-stage Alzheimer's disease with their memory and cognitive abilities, according to promising results from clinical trials [72].

Pharmacodynamics

Researchers used PET imaging to look at how LEQEMBI changed the levels of amyloid beta plaque in different parts of the brain. These levels were contrasted with those of the unaltered [73]. The researchers used the SUVR and centroid scales to measure the PET signal and determine how much amyloid beta p was present [74]. In Study 1, the effects of dose and time were looked at. LEQEMBI was found to lower amyloid beta plaque a lot more than the pill group [75]. In the same way, lecanemab greatly decreased the amounts of amyloid beta plaque in Study 2, which only looked at a single-dose regimen. h focused on a single-dose regimen. These results suggest that LEQEMBI reduces amyloid beta plaque in the brain in a beneficial way [76].

Pharmacokinetics

Lecanemab- irmb has a mean volume of distribution of 3.24 L, with a range of 3.18 to 3.30 L. Proteolytic enzymes break it down, with a clearance rate of 0.370 L/day and a range of 0.353 to 0.384 L/day [77]. The drug's terminal half-life is between 5 and 7 days. Factors such as sex, body weight, and albumin levels do not significantly affect the drug's effectiveness or safety [78]. There is no information on the impact of renal or hepatic impairment on lecanemab-irmb. However, it is predicted that these conditions would not have a substantial impact due to the drug's metabolism and elimination process [79].

Adverse drug actions

- Events that are unfavorable (those with TEAE) Adverse events during the trial were reported in three publications in allover, covering 2,729 patients (1,567 lecanemab vs. 1,162 placebo)

- Although there was no significant difference between the two groups (OR: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.25, 2.15; p = 0.57), statistically significant heterogeneity was noted (I 2 = 92%, p < 0.00001). That being said, there was statistically significant heterogeneity. The three studies that made up the study of events with Amyloid Related Imaging Abnormalities (ARIA-E) totaled 2,249 patients (1,095 lecanemab vs. 1,154 placebo).

The overall study found that the risk of ARIA-E was much higher in the group that received Lecanemab (OR: 8.95; 95% CI: 5.36–14.95; p 0.00001).

- The analysis for the occurrences of ARIA-H included a total of three articles covering 2,249 patients (1,095 receiving lecanemab vs. 1,154 receiving a placebo). It was found that there was more of the lecanemab group in ARIA-H (OR: 2.00; 95% CI: 1.53, 2.62; p 0.00001), and there was no clear heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%, p = 0.57).

Discussion

Because this protein is more frequently found in pre-plasma blasts, it may be connecting to Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Given that sample 4 has a higher risk of developing AD, it appears likely that this gene contributes to its development. We may be able to learn more about how this disease initiates if we target ABCA7 or understand how it self-regulates, particularly with regard to pre-plasma blasts. APOE, an examination of the median expression in the 450–500 signal range indicates a role for plasma cells in this disease. This contradicts the beliefs of a lot of people. Immunoglobulins have the potential to significantly impact the progression of it by targeting proteins links to the disease. Examining the roles of the various cell types that express APOE may help us develop new treatments for plasma cell diseases. APP, given that they have higher median expression of app in the signal range that causes this, it is possible that naïve b cells and early plasma cells are involves in the pathology of AD. Understanding how naïve b cells and early plasma cells affect APP expression may help uncover the mechanisms underlying AD. PSEN1: the diverse ways in which centrocytes, naive b cells, and Centro blasts express PSEN1 demonstrate the complexity of this protein's function in Alzheimer’s. Knowing where to look for signals that increase the risk to particular cell types is crucial. Tailoring interventions according to the primary cell types expressing PSEN1 may result in improves approaches to illness prevention or treatment. PSEN2a higher concentration of the protein present in early plasma cells has been links to Alzheimer’s disease. The reduces signalling capacity of bone marrow plasma cells makes it even more difficult for other cell types to become involves. It might be simpler to develop targets treatments if we investigate the function of early plasma cells in this and the various signals, they release in the bone marrow.

Different stages or subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease indicates by differences in mean expression between samples. Confidence intervals highlight statistically significant variations that knees to be investigates further. Using mean expression patterns to identify discrete subtypes aides in the development of more sophisticate understandings of AD heterogeneity and the development of individualizes treatment plans.

Aducanumab dose-relates CMAX, AUC and quick peak concentration make its pharmacokinetics predictable. The steady-state volume of distribution and expects breakdown are critical factors to consider when developing dosing strategies. These pharmacokinetic parameters must be considered when optimizing dosage schedules in order to maintain therapeutic efficacy and minimize side effects. Aducanumab's microglial clearance mechanism, lag time for maximum benefit, and pharmacodynamics emphasize long-term effects and individual variability. Specific factors influencing the lag period can be considers when tailoring the treatment, potentially improving overall therapeutic outcomes. Due, to the serious side effects of aducanumab, aria-e, and aria-h, patients must be closely monitors and controls during treatment. Developing strategies to reduce the risk of aria-e and aria-his requires to ensure aducanumab safety and tolerability in Alzheimer’s disease patients.

The pharmacokinetics, mean volume of distribution, clearance rate, and terminal half-life parameters of Lecanemab give us a full picture of how it is broken down and thrown out of the body. Looking at these pharmacokinetic parameters makes it easier to guess the drug's overall safety profile and come up with the right dosing schedules. The fact that this drug can lower amyloid beta plaque in a dose-dependent way shows how well it might work as a disease-modifying treatment. Further research on the dose-response relationships and long-term effects of Lecanemab might help in making treatment plans more effective. Unfavourable drug reactions, as well as the increases risk of aria-e and aria-h associates with this drug, necessitate close monitoring and risk management throughout treatment. Determining the variables that cause these adverse events and developing plans to reduce their effects are critical to the clinical implementation's success.

Complex gene expression patterns suggest specific cell types and genes are involves in AD. Adapting interventions to the predominant cell types expressing important genes could improve the effectiveness of treatment. Variability in mean expression across samples suggests potential subtypes or stages of Alzheimer’s disease, highlighting the importance of personalizes approaches. Aducanumab and Lecanemab are promising Alzheimer’s treatments, but adverse events must be managed carefully. This thorough analysis helps us understand the results and what they mean for Alzheimer’s disease, which opens the door for more research and new treatments.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the paper makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the many facets that comprise Alzheimer's disease for the reader. The integration of imaging results, pharmacological treatments, genetic factors, and molecular studies results in a comprehensive overview of the situation. The impact of the paper could be further increased by making improvements in terms of clarity, organization, and providing a more in-depth discussion of the results. In addition to paving the way for future research in this vital field of neuroscience and medicine, the research demonstrates that it has the potential to advance our understanding of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and the potential treatments for it.

References

- Panagiotakos G, Pasca SP. (2022). A matter of space and time: Emerging roles of disease-associated proteins in neural development. Neuron. 110(2):195-208.

- Shang X, Hill E, Zhu Z, Liu J, Ge Z, et al. (2022). Macronutrient Intake and Risk of Dementia in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Nine-Year Follow-Up Cohort Study. J Alzheimer’s Dise. 85(2):791-804.

- Niewisch MR, Giri N, McReynolds LJ, Alsaggaf R, Bhala S, et al. (2022) Disease progression and clinical outcomes in telomere biology disorders. Blood. 139(12):1807-19.

- Marde VS, Atkare UA, Gawali SV, Tiwari PL, Badole SP, et al. (2022) Alzheimer’s disease and sleep disorders: Insights into the possible disease connections and the potential therapeutic targets. Asian J Psychiatry. 68:102961.

- Freese JL, Pino D, Pleasure SJ. (2010) Wnt signaling in development and disease. Neuro bio Dise. 38(2):148-53.

- Ko YJ, Ko IG. (2021) Voluntary Wheel Running Exercise Improves Aging-Induced Sarcopenia via Activation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator-1α/Fibronectin Type III Domain-Containing Protein 5/Adenosine Monophosphate-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling Pathway. International Neuro J. 25(1):S27-34.

- Zhang X, Li J, Ma L, Xu H, Cao Y, et al. (2021) BMP4 overexpression induces the upregulation of APP/Tau and memory deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Discovery. 7(1).

- Lv C, Liu X, Liu H, Chen T, Zhang W. (2014) Geniposide Attenuates Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Memory Deficits in APP/PS1 Transgenic Mice. Curr Alzheimer Res. 11(6):580-87.

- Shentu Y, Huo Y, Feng X, Gilbert J, Wang J, et al. (2018) P3‐172: CIP2A‐PP2A SIGNALING CAUSES TAU/APP PHOSPHORYLATION, SYNAPTOPATHY AND MEMORY DEFICITS IN ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 14(7S_Part_21).

- Yang C, Zhang L. (2020) Cornel iridoid glycoside ameliorates cognitive deficits in APP/PS1/tau triple transgenic mice by attenuating amyloid‐beta, tau, and neurotrophic dysfunction. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 16(S9).

- Aso E, Ferrer I. (2016) CB2 Cannabinoid Receptor As Potential Target against Alzheimer’s Disease. Fronti Neurosci. 10.

- Tang Y, Wolk B, Nolan R, Scott CE, Kendall DA. (2021) Characterization of Subtype Selective Cannabinoid CB2 Receptor Agonists as Potential Anti-Inflammatory Agents. Pharmaceuticals. 14(4):378.

- Grether U. (2022) Targeting the Cannabinoid CB2 Receptor for Novel Anti-inflammatory Therapeutics. Scientia.

- Alaee A, Zarei R, Farnia S, Khademloo M. (2019) Relationship Between Anterior Commissure and Corpus Callosum Size and Human Intelligence in Brain MRI of Healthy Volunteers. Iranian J Radiol. 17(1).

- Ardekani BA, Bachman AH, Figarsky K, Sidtis JJ. (2013) Corpus callosum shape changes in early Alzheimer’s disease: an MRI study using the OASIS brain database. Brain Structure and Function. 219(1):343-52.

- Jiang Z, Yang H, Tang X. (2018) Deformation-based Statistical Shape Analysis of the Corpus Callosum in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 15(12):1151-60.

- Boiagina O, Stepanenko O, Lebedieva A. (2021) Correlation Between Corpus Callosum Shape and Craniometric Measurements According to Mri Data. BRAIN. Broad Res Artificial Intelligence Neurosci. 12(3):1-10.

- Yoshikai S, Sasaki H, Doh-ura K, Furuya H, Sakaki Y. (1990) Genomic organization of the human amyloid beta-protein precursor gene. Gene. 87:257-63.

- 2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. (2022) Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 18(4):700-89.

- Zhao J, Liu X, Xia W, Zhang Y, Wang C. (2020) Targeting Amyloidogenic Processing of APP in Alzheimer's Disease. Fronti Mole Neurosci. 13:137.

- LaFerla F, Green K, Oddo S. (2007) Intracellular amyloid-β in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 8:499-509.

- Masashi Asai, Chinatsu Hattori, Beáta Szabó, Noboru Sasagawa, Kei Maruyama, et al. (2003) Putative function of ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM17 as APP α-secretase. 301(1):0-235.

- Zhao J, Liu X, Xia W, Zhang Y, Wang C. (2020) Targeting Amyloidogenic Processing of APP in Alzheimer's Disease. Fronti Mole Neurosci. 13:137.

- Hampel H, Hardy J, Blennow K. (2021) The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Psychiatry. 26:5481-503.

- Pantelopulos GA, Straub JE, Thirumalai D, Sugita Y. (2018) Structure of APP-C991-99 and implications for role of extra-membrane domains in function and oligomerization. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Biomembranes 1860(9):1698-708.

- Odorčić I, Hamed MB, Lismont S. (2024) Apo and Aβ46-bound γ-secretase structures provide insights into amyloid-β processing by the APH-1B isoform. Nat Commun. 15:4479.

- Hampel H, Hardy J, Blennow K. (2021) The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Psychiatry. 26:5481-503.

- Rama N, Goldschneider D, Corset V, Lambert J, Pays L, et al. (2012) Amyloid precursor protein regulates netrin-1-mediated commissural axon outgrowth. J Biol Chem. 287:30014-23.

- Husain MA, Laurent B, Plourde M. (2021) APOE and Alzheimer's Disease: From Lipid Transport to Physiopathology and Therapeutics. Fronti Neurosci. 15:630502.

- Raulin AC, Doss SV, Trottier ZA, Ikezu TC, Bu G, et al. (2022) ApoE in Alzheimer's disease: pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies. Mole Neurodegen. 17(1):72.

- Garai K, Mustafi SM, Baban B, Frieden C. (2010) Structural differences between apolipoprotein E3 and E4 as measured by (19)F NMR. Protein science: a publication of the Protein Society, 19(1):66-74.

- Tréguier Y, Bull-Maurer A, Roingeard P. (2022) Apolipoprotein E, a Crucial Cellular Protein in the Lifecycle of Hepatitis Viruses. Inter J Mole Sci. 23(7):3676.

- Huang Y, Mahley RW. (2014) Apolipoprotein E: structure and function in lipid metabolism, neurobiology, and Alzheimer's diseases. Neurobio Dise. 72:3-12.

- Mahley RW, Weisgraber KH, Huang Y. (2009) Apolipoprotein E: structure determines function, from atherosclerosis to Alzheimer's disease to AIDS. J lipid Res. 50(1):S183-S188.

- Roses AD. (2006) On the discovery of the genetic association of Apolipoprotein E genotypes and common late-onset Alzheimer disease. J Alzheimer's Dise. JAD. 9(3):361-66.

- Bagaria J, Bagyinszky E, An SSA. (2022) Genetics, Functions, and Clinical Impact of Presenilin-1 (PSEN1) Gene. Inter J Mole Sci. 23(18):10970.

- Dai MH, Zheng H, Zeng LD, Zhang Y. (2017) The genes associated with early-onset Alzheimer's disease. Oncotarget. 9(19):15132-143.

- Van Gassen G, De Jonghe C, Pype S, Van Criekinge W, Julliams A, et al. (1999) Alzheimer’s disease associated presenilin 1 interacts with HC5 and ZETA, subunits of the catalytic 20S proteasome. Neurobiol Dis. 6:376-91.

- Laudon H, Mathews PM, Karlstrom H, Bergman A, Farmery MR, et al. (2004) Co-expressed presenilin 1 NTF and CTF form functional gamma-secretase complexes in cells devoid of full-length protein. J Neurochem. 89:44-53.

- Levitan D, Lee J, Song L, Manning R, Wong G, et al. (2001) PS1 N- and C-terminal fragments form a complex that functions in APP processing and Notch signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 98:12186-90.

- Somavarapu AK, Kepp KP. (2017) Membrane Dynamics of γ-Secretase Provides a Molecular Basis for β-Amyloid Binding and Processing. ACS Chemical Neurosci. 8(11):2424-36.

- Dai MH, Zheng H, Zeng LD, Zhang Y. (2017) The genes associated with early-onset Alzheimer's disease. Oncotarget. 9(19):15132-143.

- Cai Y, An SS, Kim S. (2015) Mutations in presenilin 2 and its implications in Alzheimer's disease and other dementia-associated disorders. Clin Interven Aging.10:1163-72.

- Zhang X, Li Y, Xu H, Zhang YW. (2014) The γ-secretase complex: from structure to function. Fronti Cell Neurosci. 8:427.

- Bhattarai P, Gunasekaran TI, Belloy ME. (2024) Rare genetic variation in fibronectin 1 (FN1) protects against APOEε4 in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 147:70.

- Cutler NR, Sramek JJ. (1998) The Role of Bridging Studies in the Development of Cholinesterase Inhibitors for Alzheimer???s Disease. CNS Drugs. 10(5):355-64.

- Purgatorio R, Gambacorta N, de Candia M, Catto M, Rullo M, et al. (2021) First-in-Class Isonipecotamide-Based Thrombin and Cholinesterase Dual Inhibitors with Potential for Alzheimer Disease. Molecules. 26(17):5208.

- Kumar V, Saha A, Roy K. (2020) In silico modeling for dual inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) enzymes in Alzheimer’s disease. Computational Biology and Chemistry. 88:107355.

- IŞIK A, ACAR ÇEVİK U, ERCETİN T, KOÇAK A. (2022) Yeni Tiyazolil-Hidrazin Türevlerinin Sentezi ve Asetilkolinesteraz (AChE) ve Bütirilkolinesteraz (BuChE) Aktivite Çalışmaları. Bilecik Şeyh Edebali Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Dergisi. 9(1):277-85.

- Martins MM, Branco PS, Ferreira LM. (2023) Enhancing the Therapeutic Effect in Alzheimer’s Disease Drugs: The role of Polypharmacology and Cholinesterase inhibitors. Chemistry Select. 8(10).

- Han JY, Besser LM, Xiong C, Kukull WA, Morris JC. (2019) Cholinesterase Inhibitors May Not Benefit Mild Cognitive Impairment and Mild Alzheimer Disease Dementia. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 33(2):87-94.

- Bazzari A, Parri H. (2019) Neuromodulators and Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity in Learning and Memory: A Steered-Glutamatergic Perspective. Brain Sci. 9(11):300.

- Koné-Paut I, Dusser P. (2020) How to handle the main drugs to treat autoinflammatory disorders and how we treat common autoinflammatory diseases. Giornale Italiano Di Dermatologia E Venereologia. 155(5).

- Fernandez FV, Crespo AB. (2020) Potential synergistic effect between Fortasyn Connect and cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with early stages (very mild and mild) of dementia due to Alzheimer disease in common medical practice: An observational, non‐interventional study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 16(S8).

- Morelli A, Guarnieri G, Sarchielli E, Vannelli G. (2018) Cell-based therapy in Alzheimer’s disease: Can human fetal cholinergic neurons “untangle the skein”? Neural Regen Res. 13(12): 2105.

- Komaroff AL. (2020) Can Infections Cause Alzheimer Disease? JAMA. 324(3):239.

- Myers A, Undem B, Kummer W. (1996) Anatomical and electrophysiological comparison of the sensory innervation of bronchial and tracheal parasympathetic ganglion neurons. J Autonomic Nervous Sys. 61(2):162-68.

- Coulombe JN, Bronner-Fraser M. (1986) Cholinergic neurones acquire adrenergic neurotransmitters when transplanted into an embryo. Nature. 324(6097):569-72.

- Asghar A, Yousuf M, Fareed G, Nazir R, Hassan A, et al. (2020) Synthesis, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) activities, and molecular docking studies of a novel compound based on combination of flurbiprofen and isoniazide. RSC Advances. 10(33): 19346-52.

- Malone K, Hancox JC. (2020) QT interval prolongation andTorsades de Pointeswith donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. 11:204209862094241.

- Kassambara A, Rème T, Jourdan M, Fest T, Hose D, et al. (2015) GenomicScape: an easy-to-use web tool for gene expression data analysis. Application to investigate the molecular events in the differentiation of B cells into plasma cells. PLoS Comp Bio. 11(1):e1004077.

- Zahavi D, AlDeghaither D, O’Connell A, Weiner LM. (2018) Enhancing antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity: a strategy for improving antibody-based immunotherapy. Antibody Therap. 1(1):7-12.

- Gandy S, Knopman DS, Sano M. (2021) Talking points for physicians, patients and caregivers considering Aduhelm® infusion and the accelerated pathway for its approval by the FDA. Mole Neurodegen. 16(1).

- Karlawish J. (2021) Aducanumab and the Business of Alzheimer Disease—Some Choice. JAMA Neurol. 78(11):1303.

- Ran Y, Xu H, Huo Y, Tian C, Yu S. (2022) Acute Profound Thrombocytopenia Within 1 Hour After Small Doses of Tirofiban. Am J Therap. 30(5):e478-e479.

- Salloway S, Cummings J. (2021) Aducanumab, Amyloid Lowering, and Slowing of Alzheimer Disease. Neurology. 97(11):543-44.

- Meyer R. (2021) Alzheimer-Wirkstoff Aducanumab: Wechselhafte Geschichte. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Online.

- Ichimata S, Yoshida K, Li J, Rogaeva E, Lang AE, et al. (2023) The molecular spectrum of amyloid‐beta (Aβ) in neurodegenerative diseases beyond Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathology.

- Vitek GE, Decourt B, Sabbagh MN. (2023) Lecanemab (BAN2401): an anti–beta-amyloid monoclonal antibody for the treatment of Alzheimer disease. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 32(2), 89–94.

- Zou Y, Qian Z, Chen Y, Qian H, Wei G, Zhang Q. (2019) Norepinephrine Inhibits Alzheimer’s Amyloid-β Peptide Aggregation and Destabilizes Amyloid-β Protofibrils: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. ACS Chemical Neurosci. 10(3):1585-94.

- Larkin HD. (2023) Lecanemab Gains FDA Approval for Early Alzheimer Disease. JAMA. 329(5):363.

- Yang J, Ding W, Zhu B, Shen S, Ran C. (2021) Reporting amyloid beta levels via bioluminescence imaging with amyloid reservoirs. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 17(S9).

- Verma S, Verma M. (2019) How can immunotherapy be used to target Amyloid Beta for treating Alzheimer Disease. Asian Pacific J Health Sci. 6(1):153-61.

- Jevtic S, Provias J. (2019) The Amyloid Precursor Protein: More than Just Amyloid- Beta. J Neuroa Experimental Neurosci. 05(01).

- Hajdú I, Végh BM, Szilágyi A, Závodszky P. (2023) Beta-Secretase 1 Recruits Amyloid-Beta Precursor Protein to ROCK2 Kinase, Resulting in Erroneous Phosphorylation and Beta-Amyloid Plaque Formation. Inter J Mole Sci. 24(13):10416.

- Beninger P. (2023) New Drug Capsule: lecanemab-irmb. Clinical Therap. 45(2):192-93.

- Lecanemab-irmb. (2023) Am J Health-System Pharmacy. 80(9):e81-e84.

- Alenazi F. (2023) Neuropharmacology of Lecanemab-irmb: A new drug granted in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuro Pharmac J. 1-3.

- AMPK: Potential Therapeutic Target for Alzheimer’s Disease. (2019). Current Protein & Peptide Sci. 21.

- Busche MA. (2019) Tau suppresses neuronal activity in vivo, even before tangles form. Brain. 142(4):843-46.

- Dolfe L, Tambaro S, Tigro H, Del Campo M, Hoozemans JJ, et al. (2018) The Bri2 and Bri3 BRICHOS Domains Interact Differently with Aβ42 and Alzheimer Amyloid Plaques. J Alzheimer’s Dise Rep. 2(1):27-39.

- Furcila D, Domínguez-Álvaro M, DeFelipe J, Alonso-Nanclares L. (2019) Subregional Density of Neurons, Neurofibrillary Tangles and Amyloid Plaques in the Hippocampus of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Fronti Neuroanatomy. 13.

- Gespach. (2012) Guidance for life cell death and colorectal neoplasia by netrin dependence receptors.

- Guntur KV, Guilherme A, Xue L, Chawla A, Czech MP. (2010) Map4k4 Negatively Regulates Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor (PPAR) γ Protein Translation by Suppressing the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Signaling Pathway in Cultured Adipocytes. J Biological Chemistry. 285(9):6595-603.

- Komaroff AL. (2020) Can Infections Cause Alzheimer Disease? JAMA. 324(3):239.

- Liu W, Li J, Yang M, Ke X, Dai Y, et al. (2022) Chemical genetic activation of the cholinergic basal forebrain hippocampal circuit rescues memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res Therap. 14(1).

- Sarkar S. (2018) Neurofibrillary tangles mediated human neuronal tauopathies: insights from fly models. J Genetics. 97(3):783-93.

- Wang X, Wang C, Pei G. (2018) α-secretase ADAM10 physically interacts with β-secretase BACE1 in neurons and regulates CHL1 proteolysis. J Mole Cell Bio. 10(5):411-22.

- Yoshikai S, Sasaki H, Doh-ura K, Furuya H, Sakaki Y. (1990) Genomic organization of the human amyloid beta-protein precursor gene. Gene. 87:257-63.

- Golde TE, Estus S, Usiak M, Younkin LH, Younkin SG. (1990) Expression of beta amyloid protein precursor mRNAs: recognition of a novel alternatively spliced form and quantitation in Alzheimer’s disease using PCR. Neuron. 4:253-67.

- Tanaka S, Shiojiri S, Takahashi Y, Kitaguchi N, Ito H, et al. (1989) Tissue-specific expression of three types of beta-protein precursor mRNA: enhancement of protease inhibitor-harboring types in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 165:1406-14.

- Mayeux R. (1999) Plasma amyloid β-peptide 1-42 and incipient Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 46:412-16.

- Lassek M, Weingarten J, Wegner M, Mueller BF, Rohmer M, et al. (2016) APP Is a Context-Sensitive Regulator of the Hippocampal Presynaptic Active Zone. PLoS Comput Biol. 12:e1004832.

- Baumkotter F, Schmidt N, Vargas C, Schilling S, Weber R, et al. (2014) Amyloid precursor protein dimerization and synaptogenic function depend on copper binding to the growth factor-like domain. J Neurosci. 34:11159-72.

- PSEN2 (presenilin 2 (Alzheimer disease 4)) (atlasgeneticsoncology.org)

- Genes known to increase the risk of Alzheimer’s may actually be an inherited form of the disorder, researchers say | CNN

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374288795_BIO_315-_Genetics-_APOE_Gene_Report