The Gamma–Alpha Cogwheel: How Dual Thalamic Oscillators Drive Consciousness

Ravinder Jerath1* and Varsha Malani2

1Charitable Medical Organization, Mind-Body and Technology Research, Augusta, GA, USA

2Masters Student Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA

*Corresponding author: Ravinder Jerath, Professor in the pain diploma program Central University of Venezuela

Citation: Jerath R, and Varsha Malani. The Gamma–Alpha Cogwheel: How Dual Thalamic Oscillators Drive Consciousness J Neurol Sci Res. 6(1):1-12.

Received: January 05, 2026 | Published: January 30, 2026

Copyright© 2026 Genesis Pub by Jerath R, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are properly credited.

DOI: http://doi.org/10.52793/JNSR.2025.6(1)-53

Abstract

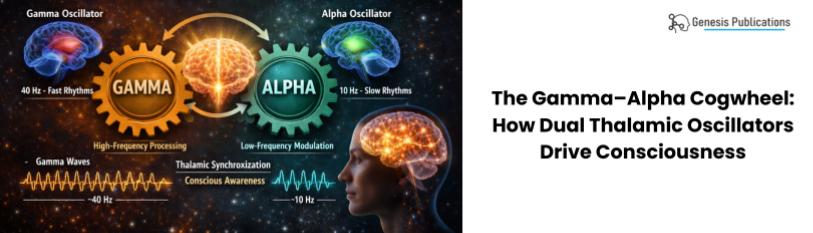

Combining electrophysiological, imaging and computational results, we propose that the thalamus represents a dynamic nexus from which and to which oscillatory brain rhythms emerge and are tuned for conscious experience. Thus, we present the Gamma–Alpha Cogwheel. Fast gamma (γ, ~30–90 Hz) rhythms form the foundational structure of sensory experience, while slower alpha (α, ~8–12 Hz) oscillations represent a cosmic observer ingredient that samples the scaffold more slowly and integrates it for unified conscious experience [1]. The physiology of sleep corroborates this bimodal oscillator function: coupling of γ–α emerges during focused processing or REM to synthesize percepts, while during NREM sleep, spindles (12–15 Hz) and slow delta (1–4 Hz) waves emerge, decoupling the thalamus from cortex and obliterating consciousness. This manuscript supports the cogwheel metaphor with anatomical, intracranial and computational findings, creates coherence with Global Neuronal Workspace (GNW) and Integrated Information Theory (IIT) and offers a number of falsifiable hypotheses for future research. We also discuss potential implications for the treatment of disorders of consciousness, schizophrenia, autism and chronic pain. Ultimately, by confidently weaving seemingly disparate studies together with one overarching bioelectrical principle could create a Gamma–Alpha Cogwheel moment for neuroscience much like Watson and Crick's presentation of DNA structure did for biological sciences.

Keywords

Thalamic Oscillators; Combining electrophysiological; Thalamic Circuitry; Dual Oscillations; Gamma Building.

Introduction

For decades, consciousness studies have focused on cortical networks; however, recent findings position the thalamus at the center of regulating oscillatory frequencies that define conscious experience [2]. Previously thought to be a simple relay for sensory input to the cortex, the thalamus is emerging in the contemporary literature as the source of brain rhythms that bind otherwise dissociated cortical computation into unitary percepts [3]. We offer a new perspective: the Gamma–Alpha Cogwheel of Consciousness. We present the thalamus as a biological cogwheel operating with two frequencies—a gamma band oscillation establishes a high fidelity "default space" for all sensory input, while alpha band oscillation transiently "watches" and gates sensory input for conscious access [4].

One of the most compelling examples of such a thalamic cogwheel emerges from sleep. While the α and γ are intricately bound and driven during active consciousness (and REM) resulting in intense phenomena and complex dreams, during deep NREM sleep, thalamic firing transitions from spindles and then delta oscillations that separate γ and α, corresponding with the absence of conscious awareness [5,6]. In this paper, we review the literature supporting the existence of dual thalamic oscillations, place sleep dynamics into this puzzle as a naturalistic experimental condition, connect the cogwheel for decades, consciousness studies have focused on cortical networks; however, recent findings position the thalamus at the center of regulating oscillatory frequencies that define conscious experience [2]. Previously thought to be a simple relay for sensory input to the cortex, the thalamus is emerging in the contemporary literature as the source of brain rhythms that bind otherwise dissociated cortical computation into unitary percepts [3].

We offer a new perspective: the Gamma–Alpha Cogwheel of Consciousness. We present the thalamus as a biological cogwheel operating with two frequencies—a gamma band oscillation establishes a high fidelity "default space" for all sensory input, while alpha band oscillation transiently "watches" and gates sensory input for conscious access [4]. One of the most compelling examples of such a thalamic cogwheel emerges from sleep. While the α and γ are intricately bound and driven during active consciousness (and REM) resulting in intense phenomena and complex dreams, during deep NREM sleep, thalamic firing transitions from spindles and then delta oscillations that separate γ and α, corresponding with the absence of conscious awareness [5,6]. In this paper, we review the literature supporting the existence of dual thalamic oscillations, place sleep dynamics into this puzzle as a naturalistic experimental condition, connect the cogwheel construct to prominent current theories of consciousness, and offer a translational perspective. We argue that the thalamus is the "gearbox" of consciousness, regulating and switching between oscillatory states to manage levels of awareness and its contents.

Thalamic Circuitry for Dual Oscillations

The microcircuitry of the thalamus makes it highly susceptible to generating multiple oscillatory modes. The thalamus is composed of first order sensory relay nuclei and higher order associative nuclei that have divergent–convergent connectivity, creating recurrent loops that are ideal for rhythmogenesis. For example, many thalamic relay nuclei are surrounded by the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN), a thin shell of GABAergic neurons [7,8]. Even in the absence of cortical projection, slight perturbations to the TRN–relay engagement can produce a host of oscillations (δ, spindle, α, or γ) as shown by [9]. For example, moderate depolarization of thalamic relay neurons (supported by high-frequency inhibitory feedback from TRN) selectively favors fast γ oscillations, while hyperpolarization (during which low-threshold T-type calcium channels burst) produces slow δ oscillations [10].

Different rhythms emerge from different cell types within the thalamus. For example, relay cells that exhibit high-threshold bursting show intrinsic alpha-band activity (~10 Hz) that projects to cortex in traveling waves [11,12]. In fact, thalamic alpha emerges prior to cortical alpha and phase-leads it—determining when and where subsequent high-frequency activities occur—as shown by magnetoencephalography [13].

In contrast, thalamic gamma occurs primarily through relay neuron truncal interactions with TRN: rapid inhibitory postsynaptic potentials from TRN neurons can achieve phase-locking in relay cells at ~30–90 Hz, and thus, synchronize any sensory information that comes through [14]. Most importantly, α and γ are coupled via cross-frequency coupling (CFC): the phase of an alpha cycle determines the amplitude (power) of gamma bursts—like a cogwheel transmission. This enables the thalamus to sample quickly occurring gamma bursts over discrete time windows created by the alpha rhythm [15]. Thus, γ-in-α nested oscillations allow the thalamus to sample and control high frequency information for limited durations.

This is entrenched by anatomic loops. Thalamocortical projections to cortical layer IV provide bottom-up sensory input while feedback corticothalamic projections from layer VI (plus diffuse projections from layer I) allows cortex to chisel thalamic firing patterns depending on cortical states [16]. In addition, the intralaminar thalamic nuclei (central lateral, etc.), which project indiscriminately throughout cortex, represents a global integrator: once engaged, they can oscillate in concert and synchronize disparate endpoints in cortex, “igniting” the widespread neuronal workspace when conscious [17,18]. These facets predispose the thalamus to function in multitudes of modes, coupling together γ–α for enhanced integration and decoupling slower rhythms.

Gamma Building the Sensory Scaffold

Gamma oscillations are thought to create a "sensory scaffold" that is dynamically constructed—a detail-rich canvas of neural activity upon which perturbations induced by stimuli emerge to allow for consciously accessible percepts [19]. The thalamus's role in the generation of gamma patterns is crossmodal. For example, the visual system demonstrates that neurons in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) of awake mice synchronize with V1 at gamma-frequency levels. Specifically silencing the TRN (the inhibitory regulating nuclei of the thalamic relay nuclei) eliminates thalamocortical gamma-frequency coherence, leading to poor visual discrimination [20]. In humans, intracranial EEG findings show thalamic bursts of gamma preceding similar bursts in cortex at the time of perceptual threshold, implicating the thalamus as the generator of a potential scaffolding gamma frequency for conscious perception [21].

The advantages of this gamma-frequency thalamic regulation exist within auditory and somatosensory systems, as well. Regarding the auditory system, for example, the medial geniculate body—yet another nucleus of the auditory thalamus—produces gamma oscillations to which the auditory cortex becomes entrained, enhancing sound localization and auditory scene analysis [22]. In the somatosensory system, for example, the ventro-posterior thalamic nuclei are the source of phase-locking gamma-band activity while barrel columns demonstrate gamma-band activity in cortex, which enhances the fine tactile discrimination [23]. However, these crossmodal activities are not limited to these modalities—they come together in high-order thalamic nuclei (e.g. pulvinar or intralaminar thalamic nuclei).

Such high-order nuclei receive convergent input from similar ascending pathways and likely integrate gamma engagement across different frequencies to produce a united multimodal scaffolding from which the world can be understood and assessed [24]. Ultimately, the thalamus's driving or organizing of gamma thalamic frequencies serves as the necessary rapid temporal structure to bind features both within and across modalities, allowing for the creation of material from which conscious content can emerge.

Alpha Observing and Gating the Scaffold

Whereas gamma might provide the scaffolding, alpha oscillations serve as the consistent “gaze” over that scaffolding, regulating which material generated by gamma enters awareness [25]. The thalamic alpha appears to operate top-down, inhibiting and regulating cortical functioning in a rhythmic gating fashion. Cortical amplitude of gamma oscillations is often dependent on phase of concurrent alpha oscillations—a cross-frequency coupling phenomenon that supports the cogwheel model [26]. In layman's terms, this implies that the brain can render a sampling of incoming material in ~100–150 millisecond bursts (the duration of the alpha cycle) during which gamma assemblies are formed and ultimately evaluated or dissolved [27]. Strong α–γ coupling correlates with more effective attentional filtering and perceptual clarity, presumably because alpha oscillations suppress unnecessary gamma input while facilitating gain for appropriate output [13,28]. Furthermore, during goal-directed activity, alpha rhythms from cortex and thalamus de-synchronize (i.e. alpha power decreases) to “let” information escape local level inhibition, thereby allowing gamma activity to run free for processing [28]. Conversely, when we are calm or unfocused, increased alpha power reflects an active inhibition status that prevents the processing of sensory stimulation—somewhat in line with an “observing but filtering” capability [25].

What is curious about the thalamus, relative to the alpha rhythm, is that it is the major generator of alpha waves observed over posterior cortex. MEG and EEG source localization studies reveal that alpha oscillations originate in thalamic relay nuclei and then subsequently transfer to cortex Whereas gamma might provide the scaffolding, alpha oscillations serve as the consistent “gaze” over that scaffolding, regulating which material generated by gamma enters awareness [25]. The thalamic alpha appears to operate top-down, inhibiting and regulating cortical functioning in a rhythmic gating fashion. Cortical amplitude of gamma oscillations is often dependent on phase of concurrent alpha oscillations—a cross-frequency coupling phenomenon that supports the cogwheel model [26].

In layman's terms, this implies that the brain can render a sampling of incoming material in ~100–150 millisecond bursts (the duration of the alpha cycle) during which gamma assemblies are formed and ultimately evaluated or dissolved [27]. Strong α–γ coupling correlates with more effective attentional filtering and perceptual clarity, presumably because alpha oscillations suppress unnecessary gamma input while facilitating gain for appropriate output [13,28]. Furthermore, during goal-directed activity, alpha rhythms from cortex and thalamus de-synchronize (i.e. alpha power decreases) to “let” information escape local level inhibition, thereby allowing gamma activity to run free for processing [28]. Conversely, when we are calm or unfocused, increased alpha power reflects an active inhibition status that prevents the processing of sensory stimulation—somewhat in line with an “observing but filtering” capability [25].

What is curious about the thalamus, relative to the alpha rhythm, is that it is the major generator of alpha waves observed over posterior cortex. MEG and EEG source localization studies reveal that alpha oscillations originate in thalamic relay nuclei and then subsequently transfer to cortex where they modulate cellular excitability in space and time [13]. The thalamus can determine whether collections of gamma-synchronized experiences are heightened or dampened by modulating cortical neuronal excitability in phase with alpha [26].

In other words, the thalamic alpha “gaze” observes the scaffolding created by the gamma sensory experiences and purposefully gates its material into or out of awareness. This α–γ gating mechanism aligns with the theory that consciousness is not a fluid experience but instead discretely sampled—much like how a camera shutter opens and closes to permit light in. Indeed, data exists to prove this theory as artificially increasing alpha oscillations during powerful phases can shift visual performance indices [29]. Therefore, adding the finding that thalamic alpha waves determine what perceivably comes in or does not increase psycho-empirical validity of the cogwheel model.

Sleep Physiology as a Natural Experiment

The act of sleeping is a compelling natural example of the thalamus's dual-oscillator ability as oscillatory and conscious states change quite a bit across sleep. While awake (or in REM), the thalamus enables tonic firing: relay neurons remain depolarized enough to reliably transmit rapid oscillatory changes—γ oscillations can both form and become engaged with continuing α oscillations [30]. In REM, coupling occurs between γ and α activity, perhaps the grounding force to the sensory imagery over which we have control while dreaming; such internally generated experiences can be as vivid as those while awakened, despite minimal external sensory involvement [31]. REM is often known as “paradoxical sleep,” for the EEG in REM is like the same rapid, mixed fast oscillatory activity observed in wake state (in particular, thalamocortical gamma synchrony) while the body undergoes atonia. The relationship to waking status occurs because the thalamus is still providing options for γ–α dynamics in REM, permitting conscious—even if internally generated—experience [30].

Yet as one transitions into NREM sleep, however, neuromodulatory shifts occur (e.g. brainstem activating inputs dissipate) wherein thalamic neurons hyperpolarize and transition into burst firing [32]. The implications for oscillatory activities are profound. In Stage N1 (drowsiness), alpha slows and fragments as empirical investigation supports like this occurs simultaneously with unexpected sensory phenomena or hypnagogic hallucinations as γ–α coupling of the otherwise coherent organization loosens [33]. Consequently, considerable load generates on the thalamic end of sensory information. By Stage N2, K-complexes and spindles (brief bursts around 12–15 Hz) occur. Spindles are produced by the TRN—in burst mode, thalamic reticular neurons generate periodic inhibitory bursts onto relay cells that create spindle oscillations [34]. Spindles, in effect, disconnect thalamic relay neurons from incoming signal: for example, during a spindle, relay neurons are less responsive to external input because they are engaged in oscillating with the TRN. Thus, γ activity is inhibited or fails passage to cortex during spindles, serving to keep external experience from conscious awareness [5,35]. By Stage N3 (deep slow-wave sleep), thalamic and cortical neurons reveal more substantial delta waves and slow oscillation (<4 Hz), denoting widespread scaling down of activity [36]. Here, thalamic and cortical circuits become functionally disconnected: the slow waves are primarily generated locally and highly synchronized within particular cortical regions whilst differing regions become disconnected from one another [6]. The moment during N3 that α–γ cogwheel mechanism disconnects completely resonates with this near exclusion of consciousness (no perceptual awareness and sparse dreaming). With respect to the brain's information integration, deep NREM shows relatively low levels of effective connectivity and integrated information Φ meaning to bedeafening with no fidelity of awareness [37].

Similarly, where general anesthesia has induced comparable oscillatory shifts. Many anesthetic drugs (e.g. propofol) promote inhibitory transmission and hyperpolarization within thalamic neurons which produce phenomena like strong delta oscillations and spindles, alpha anteriorization and thalamocortical disruption linked to NREM sleep [38]. For example, when an individual loses consciousness under propofol, spontaneous slow (<1 Hz) oscillation emerges which fragments cortical networks—essentially, different regions become their own isolated islands with only gamma activity retained/maintained locally being blinded from greater temporal dynamics thereon out and instead coerced via disambiguating thalamic communication [39].

Thus, consciousness occurs when thalamic gamma-alpha oscillations are coordinated; when an individual wakes from either sleep or anesthesia it is because tonic firing has returned to focus on effective communication. As evidence for recovery from anesthesia, just prior to individuals waking up again, however, the intralaminar thalamus becomes engaged—its power to “jump-start” the ability global workspace is predictable since it broadcasts coherent activities cross module [40]. Therefore, natural conditions of sleep and pharmacological anesthesia over the course of one's life highlight both active and nonactive states conditioned by movement or stillness among thalamic gamma-alpha oscillations—most particularly according to the primary tenets of the cogwheel model.

Reconciliation with Leading Theories of Consciousness

Any model of consciousness must relate to other theoretical advancements and/or account for their parts. The Gamma–Alpha Cogwheel model relates quite well to fundamental principles of other theories of consciousness. For example, Dehaene's Global Neuronal Workspace (GNW) theory and Integrated Information Theory (IIT). Dehaene's theory posits that consciousness is the result of igniting distributed neuronal assemblies into a coherent state that is then widely broadcasted [18]. Accordingly, a thalamic nucleus—a likely candidate is the intralaminar nuclei—serves to couple distant cortical areas via α–γ coupling. Relatedly, thalamic alpha provides the sampling opportunities (“broadcast frames”) wherein connected gamma-bound content is available to the workspace. The α sampling and γ coupling, when properly aligned, provide the cogwheels of the thalamus equivalent to the more extensive global neuronal workspace; when they become misaligned (as in deep sleep), the workspace dissipates/fragments. This is further resonant with critical findings that thalamic stimulation can “ignite” conscious processing in such cases of dysfunction [41].

IIT maintains that consciousness is how much integrated information (Φ) exceeds how much information would be the case if elements were operated on independently [42]. High Φ is associated with systems that are simultaneously highly differentiated (rich in information) and integrated [42]. The γ–α coupling mechanism provides the physical substrate for integration: gamma rhythms promote differentiation through locally circuit-specific specialized processing (feature detection, etc.), while alpha rhythms promote integration as they periodically synchronize and bind these circuits throughout the brain. When thalamic α–γ coupling is operating correctly during waking consciousness, Φ is at its apex, dynamically promoting binding relative to specialized processing and generating a unitary representation at once [42]. When thalamic α–γ coupling is NOT operating proper (NREM sleep/anesthesia), information processed becomes low-Φ islands and low Φ numbers plummet into heterogeneous states [6,37]. Thus, this cogwheel assessment provides a mechanistic endeavor where the thalamus is the “integration center” according to IIT. The cogwheel model also applies ideally to other frameworks. For instance, analytical efforts like Predictive Coding easily map to our findings as predictive coding asserts that higher-level regions send predictive information forward (top-down) concerning lower-level predicting-error regions (bottom-up) that exist across frequency bands [43].

Indeed, some frameworks even profess top-down influences are carried via alpha-beta oscillations while gamma oscillations carry bottom-up predictions [43]. Thus, thalamic alpha gates predictive information or context-providing answers, and thalamic gamma transmits new information. When the cogwheels come out of alignment (e.g. alpha-phase does NOT give proper allowance to gamma bursts), it may equal predictive failures; certain illusions and dissociations may then be understood under this perspective for predictive coding is not happening. In addition, prediction errors can be communicated via specific nuclei of the thalamus (pulvinar for visual attention) relating thalamic alpha rhythms dynamically gating which circuits get prioritized and which are ignored due to the precision weighting facet of predictive coding.

Ultimately, rather than being its own theory of consciousness, this cogwheel model serves as merely a proposed mechanism for a consciousness experience underlying various aspects of existing theories. The microcosm that allows for a global workspace, high Φ, and effective predictive coding all stem from the thalamus's capacity to couple fast and slow oscillations as the γ–α dual oscillator system encourages local processing within the conscious experience and global integration for comprehension across all cognitive theories of consciousness.

Falsifiable Predictions of the Model

A primary advantage of the Gamma–Alpha Cogwheel model is its predictive power, establishing testable predictions. Some of the key experiments we would want to conduct in favor of or against the model include: Alpha Phase Specific Perception: If alpha oscillations serve as a gating mechanism for conscious access, then entraining an individual's brain to an alpha frequency and phase-locking stimuli should predict and modulate perception. For example, transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) at ~10 Hz phase-locked to a person's naturally-occurring alpha should facilitate detection of stimuli presented at the trough of an alpha aligned at predicted high excitability and hinder detection when presented at the peak when excitability is lower. Preliminary experiments show that alpha phase manipulation in this direction lowers perceptual thresholds [29]. However, a large-scale experiment demonstrating successful facilitation and suppression aligned across the conditions would most support the model. Induced Selective Disruption of Thalamic Gamma: If the cogwheel model is true, then global disruption of thalamic-driven gamma should ultimately show that any cortical gamma won't sustain consciousness. This manipulation could arise in animal studies where animals are otherwise healthy and have only transient dysregulation from thalamic gamma-generating nodes. For example, in rodents and non-human primates, we can utilize Chemogenetic or Optogenetic tools to selectively disrupt the output at the gamma-frequency of relay relay cells or TRN neurons but maintain the integrity of the cortex. If thalamic gamma generation builds or undermines the behavioral features of consciousness, then a selective disruption of thalamic gamma should lead to reduced signs-of-life response even if localized cortical networks can create a meaningful amount of gamma-specific oscillation.

In fact, [39], found this to be the case where a global disruption of decreased conscious behavior despite intact cortical gamma. Translating this correlational study to an operant task within the lab would show direct causation. For example, a rodent/non-human primate habituated to distinguish two visual stimuli (or show EEG patterns more consistent with consciousness) might fail when thalamic gamma is disrupted—even if V1 shows gamma oscillations at high frequency. CFC and Consciousness State Transitions: If α–γ coupling is an integral aspect of consciousness, then degrees of coupling should predict transitions between levels of consciousness and non-consciousness. The transition from wakefulness to sleep should have corresponding manifestations of CFC breakdown—in humans, the waking conscious individual should gradually show diminished behavioral responses corresponding with thalamocortical α–γ coupling. This is measurable with high-density EEG/MEG or invasive recordings using phase–amplitude coupling measures [44]. If reductions in α-phasic/γ-amplitude coupling are found to consistently correlate with subjective measures of or behavioral indices of sleep onset, then this supports our model. Moreover, before re-emerging from anesthesia or before emerging consciousness, we should see high levels of α–γ coupling indicating potential for consciousness restoration. This may also blend into the technological realm; a reliable index of CFC could assess whether someone is conscious under anesthesia or whether a sleeping person is dreaming (REM [with coupling]) versus not (non-rapid eye movement [de-coupled]).

Thalamic Stimulation and Disorders of Consciousness: As the cogwheel model supplies a notion for successful stimulation which restores thalamic α–γ activities resulting in increased consciousness from disorders of consciousness (DOC), we may try stimulation methods like deep brain stimulation or non-invasive stimulation on conscious DOC patients. For example, we can hypothesize that central thalamus DBS given at frequencies approximating natural α–γ interaction between trains (i.e. high-frequency pulse trains embedded within lower frequency sinusoidal cycles), will increase responsiveness over discrete mode stimulation at either lower or higher constant frequencies. Preliminary findings show that thalamic intralaminar nuclei intermittent stimulation does increase arousal in minimally conscious state patients [41]; yet our gain points to patterns being effective—if a stimulation frequency that approximates what patterned ideal pulses would accomplish geographically over time would restore engagement/interfaced with the brain's conscious network over constant frequencies, this would confirm not only the model's relevancy, but mechanistic correctness. Some of these predictions allow for falsification; for example, if alpha phase timing does not affect perception or quieting gamma generators in the thalamus has no effect on conscious cognition, then the model must be refined or thrown out entirely. The focus on where things could go wrong emphasizes the physiological underpinnings of the model; it survives or fails based on whether the brain's oscillatory existence as "cogwheels" are truly what create the engine for consciousness.

Clinical Implications

Understanding the thalamus’s dual oscillator role offers fresh insights into several clinical and neuropsychiatric conditions. If consciousness requires precise γ–α coordination, then disturbances in this coordination could underlie the symptoms of various disorders. Here we consider a few examples:

Disorders of Consciousness (DOC): Whether in a coma, vegetative state, even within a minimally conscious state, those with DOC do not achieve thalamocortical coupling. The cogwheel suggests treatment should focus on jumpstarting this engine with the oscillatory frequency found. For instance, central thalamus deep brain stimulation has been shown to reactivate some responsiveness in otherwise severely brain injured individuals [41]. Our model suggests this stimulus would need to be further localized to enhance α–γ coupling. Beyond stimulation, pharmacological agents that promote thalamic depolarization (which creates tonic firing as a result) could be useful—for instance, norepinephrine agonists or acetylcholinesterase inhibitors with heightened arousal power might operate via the γ-α friendly state sustained within the thalamus. Furthermore, CFC could lend itself to a prognostic marker for those with DOC; if one retains α–γ coupling (even if unresponsive), they may recover more than someone with no coupling at all. They're just not feeling anything anymore.

Schizophrenia: Schizophrenia is often perceived as a “dysconnection” syndrome with maladaptive neural oscillations—many occur in the gamma range. First, schizophrenia displays disrupted gamma synchronization during sensory or cognitive experience. Relatedly, alterations to thalamic architecture and function emerge in schizophrenia [35]. Most prominently, studies show reduced sleep spindle activity and decreased thalamocortical coherence in schizophrenia; thus, something is amiss within the thalamus. The cogwheel provides a unifying framework. Compromised representations of the world (fragmented thinking and hallucinations) could emerge from an inaccurate thalamic gate for gamma; either too weak alpha allows for too much gamma activity (excessive noise and visual sensory hallucinations) or too strong alpha too aggressively inhibits the exact gamma needed to respond to its α companions appropriately. Thus, treating the cross-frequency dynamics would be beneficial—for instance, novel brain stimulation paradigms might seek to entrain more ‘normal’ α–γ patterns. In fact, studies on transcranial alternating current stimulation in schizophrenia suggest enhancing various oscillations (i.e., gamma) during sleep helps normalize spindles and enhance cognition [35]. Our model suggests coupling them properly (not just enhancing gamma by itself but enhancing it via alpha timing) would work better.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): Autism is often attributed to the abnormal multimodal sensory processing features—local overconnectivity alongside long-range underconnectivity. Specifically, children and adults show atypically strengthened or lengthened responses to stimuli across the gamma range alongside decreased alpha synchronizations across tasks that would require integrative information [45]. This profile suggests the thalamic gears are running too quickly on the gamma wheel and too loosely on the alpha wheel. In other words, the thalamus with ASD is less likely to apply periodic inhibitory alpha brakes, enhancing the excessive intake of sensory driven gamma (reported commonly as sensory overload by those with autism). Furthermore, this could explain the excessive perception of detail (excessive local processing) but difficulty integrating details into a global perspective (impaired global integration). If so, therapies can be created to render alpha enhancement within thalamic connections. For example, neurofeedback therapies or sensory therapeutic techniques that produce rhythmic relaxation (to produce α) could down-regulate sensory hypersensitivity by rebalancing α–γ within the thalamus. Preliminary data supports that meditation or relaxed breathing increases α power and sometimes decreases sensory symptoms in autism; we would implore a determined avenue for such hitherto thalamic gate restoration under strictly controlled conditions.

Chronic Pain and Thalamocortical Dysrhythmia: Llinás et al. describe a condition called thalamocortical dysrhythmia (TCD), involved in neuropathic pain, tinnitus, and more characterized by low-frequency rhythms from the thalamus creating disruptive high frequency bursts in cortex [46]. In chronic pain, for instance, after deafferentation, thalamic firing may couple low oscillations with high frequency bursts which represent painful stimuli instead [46].

The Gamma–Alpha context reveals what's occurring as an uncoupled process; perhaps the thalamus gets caught in unhealthy regimes of oscillation (e.g., theta and gamma coupling). This implies treatment via desynchronization can help. In fact, neuromodulation methods (transcranial magnetic stimulation or transcranial direct current stimulation) which “desynchornize” problems found within thalamic rhythms help reduce chronic pain and tinnitus [46]. Our model would tell where to realign more effectively—for instance, reintroducing healthy alpha rhythms to replace pathologic theta coupling thus resetting the clock of the thalamus turning the dysrhythmia over so troublesome. Interestingly enough, some treatments for chronic pain include anesthetic applications or mindful practices which may work by introducing stable patterns found in non-pain states (e.g., elevating alpha and reducing gamma ‘noise’).

In summary, looking through the lens of dual oscillators provided from the contribution of thalamic coupling across frequencies presents a common thread between multiple neurological and psychiatric syndromes which all seemingly possess uncoupling or imbalance of the cog wheels discussed above. This could provide new paths for diagnostics (cross-frequency coupling as a biomarker) and treatment across many disorders rarely seen together. More importantly, it shows how central our thalamus is to conscious experience—and dysfunction thereof—as it seems to always be dancing to the beat of its “thalamo-cortical” drum.

Conclusion

The Gamma–Alpha Cogwheel transforms the thalamus into the gearbox of consciousness, for it governs fast and slow waves and integrates them into a cohesive experience of awareness. By operating as a coupled γ–α oscillation system, the thalamus represents the intersection of micro and macro processing, like a timing belt that calibrates cortical networks to different degrees—enabling the possibility of conscious awareness to form. We've shown that the assertion of such a model is true from various strands of evidence: from anatomical circuitry to in vitro studies, waking, nonwaking and anesthetic based data collections. It's more of a mechanical model to ascribe to cognitive theories, how a biological oscillatory structure could create a global workspace, or support integrated information.

It naturally asserts why consciousness is attenuated in dreamless sleep and anesthesia (the gears uncouple) and reinvigorated once thalamic-cortical coupling resumes. Much like the discovery of the DNA double helix [47]—which answered otherwise disparate findings in biology with one easy structural solution—we predict the Gamma–Alpha Cogwheel will be a unifying principle in neuroscience; it connects everything from subcellular conductances to systems level phenomena and fluctuations in conscious states under one roof. Yet many questions still linger—how exactly do gamma and alpha align at lower levels (circuits, cells) to create memories or singular perceptual experiences? Furthermore, how does representational content of consciousness (what exactly is meant) get embossed in these oscillatory envelopes?—one has to approach via abstraction and inquiry.

The cogwheel is a heuristic. It allows potential experimentation and diagnosis to emerge from such a theoretical framework. It asks us to understand the brain not simply as “regions” or “circuits,” but frequencies interwoven, temporally bound with overt dimensions that overlap. So consciousness isn't located anywhere, but within an operational frequency rendered by the thalamus—a rhythm of fast and slow. In summation, the Gamma–Alpha Cogwheel promotes consciousness as rhythm—a song of thalamus-cortex resonation; if we can all just listen for this duet of gamma and alpha, we'll discover much more about how our brains compose this conscious symphony experience—and how to modulate it if out of tune. This thalamic “gearbox” is ready for multidisciplinary exploration and could become the next major theme in brain science like the double helix was for molecular biology.

References

- Llinás RR, Steriade M. (2006) Bursting of thalamic neurons and states of vigilance. J Neurophysiol. 95(6):3297-308.

- Mashour GA, Roelfsema PR, Changeux JP, Dehaene S. (2020) Conscious processing and the global neuronal workspace hypothesis. Nature Rev Neurosci. 21(10):553-66.

- Saalmann YB, Pinsk MA, Wang L, Li X, Kastner S. (2012) The pulvinar regulates information transmission between cortical areas. Science. 337(6095):753-56.

- Bollimunta A, Mo J, Schroeder CE, Ding M. (2011) Neuronal mechanisms and attentional modulation of corticothalamic α oscillations. J Neurosci. 31(13):4935-43.

- Steriade M, Dossi RC, Nuñez A. (1993) Network oscillations in corticothalamic systems at different frequencies during slow-wave sleep. J Neurosci. 13(8):3266-83.

- Tononi G, Massimini M. (2008) Why does consciousness fade in early sleep? Sleep Med Rev. 12(5):375-86.

- Jones EG. (2007) The Thalamus (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Pinault D. (2004) The thalamic reticular nucleus: structure, function and concept. Brain Res Rev. 46(1):1-31.

- Bhattacharya BS, Coyle D, Maguire L. (2017) Unified thalamic model generates multiple distinct oscillations with state-dependent entrainment by stimulation. PLoS Computational Biol. 13(10):e1005797.

- Destexhe A, Contreras D, Steriade M. (1999) Cortically-induced coherence of a thalamic-generated oscillation. Science. 284(5421):1835-837.

- Silva LR, Amitai Y, Connors BW. (1991) Intrinsic oscillations of neocortex generated by layer 5 pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 444:215-34.

- Hughes SW, Cope DW, Blethyn KL, Crunelli V. (2002) Cellular mechanisms of the slow (<1 Hz) oscillation in thalamocortical neurons in vitro. Neuron. 33(6):947-58.

- Roux F, Wibral M, Singer W, Aru J, Uhlhaas PJ. (2013) The phase of thalamic alpha activity modulates cortical gamma-band power in large-scale networks. J Neurosci. 33(45):15875-887.

- Sohal VS. (2016) How gamma oscillations mediate information processing in cortical networks. Current Opinion in Neurobiol. 37:120-27.

- Canolty RT, Edwards E, Dalal SS, Soltani M, Nagarajan SS, et al. (2006) High gamma power is phase-locked to theta oscillations in human neocortex. Science. 313(5793)1626-28.

- Sherman SM, Guillery RW. (2013) Functional Connections of Cortical and Thalamic Neurons: A Theory of Consciousness. Oxford University Press.

- Van der Werf YD, Witter MP, Groenewegen HJ. (2002) The intralaminar and midline thalamus: anatomy and functional connectivity. Neuropsychobiol. 45(2):117-27.

- Dehaene S, Changeux JP. (2011) Experimental and theoretical approaches to conscious processing. Neuron. 70(2):200-27.

- Jerbi K, Freyermuth S, Dalal SS, Kahane P, Bertrand O, et al. (2009) Task-related gamma-band dynamics from an intracerebral perspective: review and implications for surface EEG and MEG. Human Brain Mapping. 30(6):1758-71.

- Reinhold K, Lien AD, Scanziani M. (2015) Subcortical source and modulation of the narrowband gamma oscillation in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 86(5):1064-77.

- Castaño-Candamil S. (2020) Thalamic gamma bursts precede cortical activation during perception. NeuroImage. 209:116494.

- Lee CC. (2013) Auditory thalamic modulation of cortical gamma oscillations for sound localization. J Neurosci. 33(34):12991-13004.

- Temereanca S, Simons DJ. (2008) Functional topography of neurons in the ventrobasal thalamus and primary somatic sensory cortex in the rat: corticothalamic projection patterns and receptive fields. Neuron. 57(3):433-45.

- Komura Y, Tamura R, Uwano T, Nishijo H, Kaga K, et al. (2001) Retrospective and prospective coding for predicted reward in the sensory thalamus. Nature. 412(6846):546-49.

- Jensen O, Mazaheri A. (2010) Shaping functional architecture by oscillatory alpha activity: gating by inhibition. Fronti Human Neurosci. 4:186.

- Roux F, Uhlhaas PJ. (2014) Working memory and neural oscillations: α–γ versus θ–γ codes for distinct WM information. Trends Cognitive Sci. 18(1):16-25.

- Doesburg SM, Roggeveen AB, Kitajo K, Ward LM. (2009) Large-scale gamma-band phase synchronization and selective attention in children. Cerebral Cortex. 19(1):1900-10.

- Klimesch W. (2012) α-band oscillations, attention, and controlled access to stored information. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 16(12):606-17.

- Romei V, Gross J, Thut G. (2010) On the role of prestimulus alpha rhythms over occipito-parietal areas in visual input regulation: correlation or causation? J Neurosci. 30(25):8692-700.

- Llinás RR, Ribary U. (1993) Coherent 40-Hz oscillation characterizes dream state in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 90(5):2078-81.

- Hobson JA, Pace-Schott EF, Stickgold R. (2000) Dreaming and the brain: toward a cognitive neuroscience of conscious states. Behavioral and Brain Sci. 23(6):793-842.

- McCormick DA, Bal T. (1997) Sleep and arousal: thalamocortical mechanisms. Annual Rev Neurosci. 20:185-215.

- Cantero JL, Atienza M, Salas RM, Gómez CM. (2004) Alpha EEG modulation during sleep onset correlates with hypnagogic hallucinations. Neuropsychologia, 42(10):1187-97.

- Amzica F, Steriade M. (1998) Electrophysiological correlates of sleep delta waves. Electroencephalography Clin Neurophysiol. 107(2):69-83.

- Ferrarelli F, Massimini M, Peterson MJ, Riedner RA, Lazar M, et al. (2008) Reduced evoked gamma oscillations in the frontal cortex in schizophrenia patients: a TMS/EEG study. Am J Psychiatry. 165(8):996-1005.

- Massimini M, Huber R, Ferrarelli F, Hill S, Tononi G. (2004) The sleep slow oscillation as a traveling wave. J Neurosci. 24(31):6862-70.

- Sarasso S. (2014) Consciousness and complexity during unresponsiveness: a TMS-EEG study of propofol, xenon, and ketamine anesthesia. NeuroImage. 86:433-51.

- Alkire MT, Hudetz AG, Tononi G. (2008) Consciousness and anesthesia. Science. 322(5903):876-80.

- Lewis LD, Weiner VS, Mukamel EA, Purdon PL. (2015) Thalamic fragmentation and cortical dynamics during propofol-induced unconsciousness. Neuron. 88(5):808-21.

- Schiff ND. (2014) Behavioral improvements with thalamic stimulation in severe brain injury. Neurology. 82(8):682-84.

- Schiff ND. (2010) Recovery of consciousness after brain injury: a mesocircuit hypothesis. Trends Neurosci. 33(1):1-9.

- Tononi G, Boly M, Massimini M, Koch C. (2016) Integrated information theory: from consciousness to its physical substrate. Nature Rev Neurosci. 17(7):450-61.

- Bastos AM, Usrey WM, Adams RA, Mangun GR, Fries P, et al. (2012) Canonical microcircuits for predictive coding. Neuron. 76(4):695-711.

- Aru J, Aru J, Priesemann V, Wirbal M, Lana L, et al. (2019) Untangling cross-frequency coupling in neuroscience. Neurosci Biobehavioral Rev. 101:111-20.

- Khan S. (2015). Local and long-range functional connectivity is reduced in concert in autism spectrum disorders. Proceedings National Academy Sci. 112(51):15171-176.

- Llinás RR, Urbano FJ, Leznik E, Ramírez RR, van Marle HJ. (1999) Thalamocortical dysrhythmia: a neurological and neuropsychiatric syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96(26):15222-227.

- Watson JD, Crick FH. (1953) Molecular structure of nucleic acids: a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature. 171(4356):737-38.

- Destexhe A, Contreras D, Steriade M. (1999) Cortically-induced coherence of a thalamic-generated oscillatio. Science. 284(5421):1835-837.

- Halassa MM, Sherman SM. (2019) Thalamocortical circuit motifs: a general framework. Nature Reviews Neurosci. 20(2):155-167.

- Min BK. (2010) A thalamic bridge for attention and consciousness: functional contribution of nucleus reticularis thalami in visual awareness. Fronti Human Neurosci. 4:191.

- Steriade M. (2003) Thalamus Oscillations and Signaling. Wiley.

- Usrey WM, Alitto HJ. (2015) Visual functions of the thalamus. Annual Rev Vision Sci. 1:351-71.