Rhinorrhoea Secondary to Spontaneous Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak: A Case Report

Ahmed Yagoub Ahmed Mohammed1* and Omer Yahia2

1General Physician MBBS USMLE Step1, USMLE Step2

2El Rebat University Sudan faculty of medicine, USMLE step 1, USMLE step2

*Corresponding author: Ahmed Yagoub Ahmed Mohammed, General Physician MBBS USMLE Step1, USMLE Step

Citation: Mohammed AYA, Yahia O. Rhinorrhoea Secondary to Spontaneous Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak: A Case Report. J Neurol Sci Res. 5(1):1-6.

Received: January 07, 2025 | Published: January 18, 2025

Copyright©️ 2025 genesis pub by Mohammed AYA, et al. BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International License. This allows others distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as they credit the authors for the original creation.

DOI: http://doi.org/10.52793/JNSRR.2025.5(1)-42

Abstract

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhoea refers to the loss of CSF through the nasal cavity. The primary cause of a CSF rhinorrhoea can be classified as either spontaneous, with causes such as congenital anatomical defects related to the temporal bone, skull base, or dura mater, or non-spontaneous, with causes such as surgical or accidental trauma, tumours, or exposure to radiation therapy involving the base of the skull. The current literature describes that patients who present with CSF rhinorrhoea require immediate surgical repair if conservative management fails. Definitive treatment most commonly involves an endoscopic transsphenoidal repair of the defect. However, the available literature describes the challenges often faced during the diagnosis and management of this condition. Here, we present a case of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea in a previously healthy 49-year-old female that required surgical intervention due to failure of conservative management.

Keywords

Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea; CSF; Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea

Introduction

A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhoea occurs following acquired communication between the central nervous system (CNS) and the external environment. This presentation is, therefore, defined as the end product of both the active and passive filtration of plasma at the choroid plexus [1]. The primary cause of a CSF rhinorrhoea can be classified as either spontaneous, with causes such as congenital anatomical defects related to the temporal bone, skull base, or dura mater, or non-spontaneous, with causes such as surgical or accidental trauma, tumours, or exposure to radiation therapy involving the base of the skull [2,3]. The most prevalent cause is trauma, both iatrogenic and non-iatrogenic, with figures estimating that trauma is responsible for between 80% and 90% of CSF fistulas [4].

The current literature describes that patients who present with CSF rhinorrhoea require immediate surgical repair. However, many techniques and materials may be adopted to achieve this and attain effective closure of the CSF fistula. In patients with high-flow CSF fistulas, improved outcomes have been observed with multi-layered, vascularised repairs as this decrease the risk of postoperative CSF leaks. On the other hand, patients that present with idiopathic intracranial hypertension demand long-term management following surgical interventions to address the underlying disease process [5].

Early diagnosis and effective management are necessitated to prevent the life-threatening complications associated with CSF rhinorrhoea, including bacterial meningitis and brain abscesses. However, the available literature describes the challenges often faced during the diagnosis of this condition. As depicted in previous case reports, patients that present with unilateral clear nasal discharge alongside nonspecific headache symptoms should be suspected for CSF rhinorrhoea. Other symptoms, such as alterations in mental status, seizure and meningitis are also prevalent [6]. We present a case of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea in a previously healthy 49-year-old obese female.

Case Presentation

A 49 years old female patient, with a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and Schizoaffective disorder, presented to the emergency department with right facial asymmetry and body weakness on the right side. A comprehensive assessment of her current medical history was undertaken. On admission, the patient was hypertensive (190/95), had a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 141 mmHg, a heart rate of 76 bpm, and stable blood oxygen saturation (SO2). The patient also presented with an elevated BMI.

An initial MRI of the patient’s brain (01/06/2022) revealed an acute infarct in the left frontoparietal region and moderate attenuation of the M2 segment of the left middle cerebral artery. After a discussion with the patient’s family, it was noted that the onset of symptoms was more than 24 hours prior to her presentation to the hospital. Following the MRI, the patient’s case was discussed with the neurology team and she was subsequently admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for 24 hours before being transferred to the medical ward, as per the acute stroke protocol. Conservative medical treatment was administered with ongoing observation.

Four days later (05/06/2022) the CT scan showed an acute to subacute infarct in the left frontoparietal region. A new area of hypodensity was also observed in the left ganglion-capsular region, measuring 3cm by 1.7cm. Nonetheless, there was no evidence of a haemorrhagic transformation or mass effect. At this time, the patient was alert and sitting in bed and was able to recall all her family members; however, she was not oriented to the time or place. Furthermore, there was impairment in her comprehension and she presented with aphasia, dysphagia, and impairments in her cognition and memory.

Rehabilitation was initiated and the patient was admitted to the rehabilitation centre to begin an intensive programme (09/06/2022). Two weeks later, the patient began to experience a clear watery nasal discharge alongside left ear discomfort. The patient was referred to the ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist and CSF leakage was highly suspected. As a result, the patient was admitted to adult neurology for further observation and management, where an MRI brain showed a temporal bone defect. The neurology specialist recommended surgical treatment, specifically a craniotomy with the evacuation of the meningoencephalocele and a cranioplasty of the skull-based defect. A duroplasty was also advised. A second opinion was sought, which warranted a CT scan of the patient’s sinus to be done. This confirmed the CSF leakage diagnosis and the patient and her family agreed to proceed with Transsphenoidal surgery.

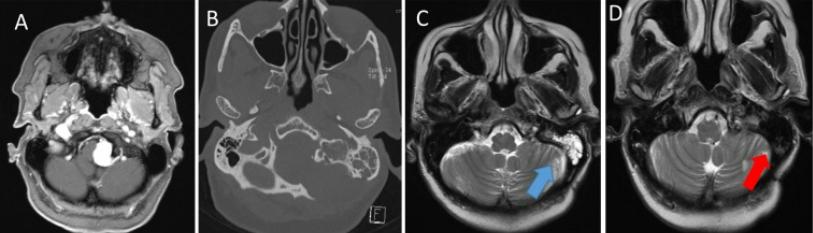

Figure 1: MRI of the brain. The scans demonstrate a small transsphenoidal temporal lobe encephalocele through the left lateral craniopharyngeal canal with associated drainage of CSF into the left side of the sphenoid sinus.

Discussion

CSF rhinorrhoea arises following abnormal communication between the subarachnoid space and a defect in the skull base. This induces the loss of CSF through the nasal cavity and can be categorised as either spontaneous or non-spontaneous. Spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea also referred to as non-traumatic CSF rhinorrhoea, is extremely rare and accounts for only 4% of all reported cases [7-9]. This unique clinical manifestation has been associated with elevated intracranial pressure (ICH) and an elevated BMI. It is also of note that spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea is more commonly observed in females who are both middle-aged and overweight [10]. Here, we presented a case of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea in a 49-year-old female patient with an elevated BMI.

Despite the numerous case studies and series describing patients with CSF rhinorrhoea, the pathogenesis of this presentation still remains unclear. Previous studies have hypothesised that prolonged ICH may trigger defects to present in a patient’s skull over time. These defects paired with the continued ICH can result in herniation of the patient’s dura mater in the bony defects. In turn, this weakens the dura mater and increases its susceptibility to dural tears and a dural-mucosal fistula [11].

Obesity has also been suggested as a prevalent cause of CSF rhinorrhoea as it triggers augmented intraabdominal pressure. In turn, this elevates the diaphragm and increases both the plural and cardiac pressures. Badia et al. initially indicated that a relationship may exist between obese females and the risk of developing a primary spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea in a 2001 case review. In this 20-patient case series, all patients were clinically obese (BMI >30kg/m2) and presented with spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea [12]. Sugermann et al. substantiate this paradigm and proposed a mechanism for this relationship. In this review, it was suggested that the elevated BMI in obese patients raises intraabdominal and intrathoracic pressure. As a result, this may result in an increase in cardiac-filling pressure and a subsequent impediment on the venous return from the brain. This induces the ICH typically observed in patients with CSF rhinorrhea [13]. In the case described in this report, the patient presented with an elevated BMI and complained of headaches that were exacerbated when she bent over. This potentially indicates ICH, although the patient had no signs of ICH on examination.

Several diagnostic mechanisms are depicted in the current literature for the diagnosis of CSF rhinorrhoea. Nonetheless, the gold standard approach comprises the use of beta-2-transferrin or beta-2 trace protein, two biomarkers exclusively found in the CSF and perilymphatic fluid. The adoption of this protein in the detection of CSF leakage was first described in 1979 by Meurman et al. and has since been extensively utilised by healthcare professionals for the diagnosis of CSF rhinorrhoea and skull-base cerebrospinal fluid fistulas. This approach remains the gold standard due to its reported sensitivity of 94% to 100% and specificity of 98% to 100% [14]. In the case of our patient, we were unable to assess beta-2 transferrin and resorted to using comparative blood glucose concentrations of the draining fluid to the blood. The presence of glucose in secretions strongly indicates the presence of CSF. However, this is not recommended as a confirmatory test due to low diagnostic specificity and sensitivity [15]. Additionally, a high prevalence of false-negative results is reported in cases of bacterial contamination and a high prevalence of false-positive results in diabetic patients. Therefore, the detection of glucose in CSF rhinorrhoea cannot be used on its own to diagnose a CSF leak and requires concurrent clinical and radiographic evidence.

Radiographic analyses are typically necessitated for the primary diagnosis of CSF leaks, including non-invasive high resolution CT and MRI imaging alongside clinical examinations [16]. Both imaging investigations are reliable approaches to differentiate between spontaneous and nonspontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea and can assist in the localisation of the leaks. This is critical in patients who present with fracturs of surrounding bone or tumors but do not present with a leakage [7]. CT/MR cisternography, although invasive, is deemed the gold standard for the detection of CSF leaks, and is capable of identify the site, size, and quantity of the leak, particularly in the presence of multiple bony defects [17]. However, due to the invasive nature of this imaging procedure, it is not advised and is considered unnecessary in patients where a diagnosis of CSF rhinorrhoea is supporting by the clinical presentation and CT/MRI findings [7].

In the treatment of CSF rhinorrhoea, a conservative approach is recommended initially; however, if these fails, surgical interventions are necessitated to prevent long-lasting and life-threatening complications. Conservative treatment comprises the administration of acetazolamide, prolonged bed rest, and elevation of the head to decrease intracranial pressure. Surgical interventions, on the other hand, include either endoscopic or extracranial approaches or an intracranial approach. An endoscopic approach is usually favoured due to a lower rate of morbidity and increased success rates of 90% to 100% compared with the increased morbidity and 60% to 80% success rate with an intracranial approach [7, 18].

The current recommendations and clinical guidelines suggest that the initial management of CSF rhinorrhoea involve endoscopic repair, with extracranial repair being adopted following failure of endoscopic repair. Adjunctive therapies, such as antibiotics, diuretics, lumbar drains, and prolonged bed rest with elevation of the head, may be considered alongside the recommended management to further reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with CSF rhinorrhea [19].

Conclusions

Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are necessitated in patients presenting with CSF rhinorrhoea to prevent complications, such as meningitis, intracranial sepsis, and abscesses, which are associated with high mortality rates. Spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea is a rare clinical presentation usually associated with an elevated BMI and ICH. The gold standard for the detection of CSF in secretions is beta-2 transferrin testing; however, clinical examination and CT/MRI imaging findings are sufficient to confirm a diagnosis. With the successful surgical repair of a CSF leak and an uneventful postoperative period, patients usually have a favourable prognosis.

Disclosures

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study.