Full-Arch Maxillary Rehabilitation Using the Bone Truss Bridge in a Severely Compromised Maxilla: A Clinical Case Report

Henri Diederich1*, Mohamed Seghir Babouche2 and Vladislavs AnanJevs3

1Doctor in dental medecine 114 av de la Faiencerie, L- 1511 Luxembourg

2Promotion Rato, El Eulma 19600, Algeria

3Rajna iela, 1-1N, Liepaja, LV3401, Latvia

*Corresponding author: Henri Diederich, Doctor in dental medecine 114 av de la Faiencerie, L- 1511 Luxembourg

Citation: Diederich H, Babouche MS, Anajevs V. Full-Arch Maxillary Rehabilitation Using the Bone Truss Bridge in a Severely Compromised Maxilla: A Clinical Case Report. J Oral Med and Dent Res. 6(3):1-10.

Received: December 01, 2025 | Published: December 28, 2025

Copyright©️ 2025 Genesis Pub by Diederich H. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are properly credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.52793/JOMDR.2025.6(3)-109

Abstract

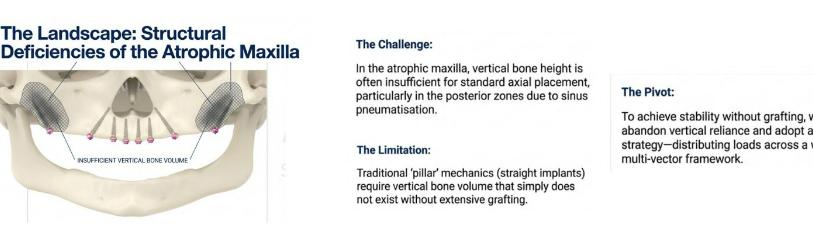

Rehabilitation of the severely atrophic maxilla remains a major clinical challenge due to limited bone volume, sinus pneumatization, and reduced bone density. Conventional treatment options such as extensive bone grafting, sinus augmentation, zygomatic implants, or subperiosteal frameworks are effective but often associated with increased morbidity, prolonged treatment time, and high financial burden. This case report describes the rehabilitation of a compromised maxilla using the Bone Truss Bridge (BTB) approach, a minimally invasive, graftless full-arch protocol based on bone-driven implantology principles. Patient cases illustrating functional and aesthetic rehabilitation achieved within weeks, demonstrating the potential of the BTB approach as an alternative to more invasive procedures in selected patients.

Keywords

Rehabilitation; Zygomatic Implants; Bone Truss Bridge; Subperiosteal Implants

Introduction

Rehabilitation of the compromised maxilla is particularly demanding because residual bone is frequently thin, resorbed, and pneumatized, limiting the placement of conventional implants and increasing both biological and economic treatment burdens. Traditional treatment modalities—including bilateral sinus floor elevation, large bone grafts, zygomatic implants, or subperiosteal implants—have shown predictable outcomes but are often associated with multiple surgical stages, higher morbidity [Ref 1], extended healing periods [2,3], and significant costs [4,5]. These factors may reduce patient acceptance, especially in elderly or medically compromised individuals.

Consequently, there is growing interest in minimally invasive, graftless concepts [6,7] that can achieve high primary stability, allow early or immediate loading [9-11], and shorten overall treatment time [Ref 8]. The Bone Truss Bridge (BTB) approach addresses this clinical need by using strategically anchored one-piece implants in residual cortical bone to create a rigid, triangulated load-bearing framework capable of supporting a full-arch fixed prosthesis.

Rationale for the Bone Truss Bridge (BTB)

The Bone Truss Bridge (BTB) approach is based on bone-driven implantology, in which implant placement is dictated by the availability and quality of native bone rather than by prosthetically ideal positions that require extensive augmentation. By anchoring implants in dense cortical regions such as the pterygoid plates [6,7], nasal floor, and anterior maxilla, the BTB achieves high primary stability and enables early functional loading [9-11] without the need for grafting procedures.

Biomechanical Principles

High primary stability is a requisite for immediate or early loading and is influenced by bone density, cortical engagement and implant macro-design [12-15]. From a biomechanical perspective, reducing micro motion and converting shear stresses into compressive forces improves osseointegration and long-term stability [13,16,17].

Implant Design Discussion

One-piece tissue-level implants eliminate the implant–abutment microgap at bone level, reducing crestal bone re-modeling associated with bacterial leakage and mechanical pumping effects [18,19]. Progressive and aggressive thread designs have been shown to enhance primary stability and allow predictable immediate functional loading protocols [20].

Surgical Principles

The Bone Truss Bridge can be described as a graft less full-arch protocol characterized by:

- Placement of multiple long, narrow, one-piece tissue-level implants and strategic engagement of cortical bone areas, including:

- Pterygoid plates for posterior anchorage and resistance to lateral forces.

- Trans-nasal and anterior maxillary cortices for cross-arch stabilization

- Splinting of implants with a rigid, CAD/CAM-fabricated prosthetic framework designed according to truss engineering principles.

- Crestal access with flap elevation, avoiding sinus grafting and large onlay grafts in most cases, which reduces surgical time, postoperative morbidity, and overall treatment duration.

This configuration converts individual implant loads into a distributed, triangulated force system, reducing stress on each implant and enabling stable rehabilitation even in severely atrophic maxillae.

Prosthetic and Biomechanical Considerations

Immediate or very early loading [12,20] is feasible due to the rigid splinting effect of the milled metal framework, which stabilizes the implants under functional loading in a truss configuration. Angulated screw channels and a screw-retained design allow passive fit, retrievability, and accurate occlusal adjustment while optimizing load distribution across the arch.

Case Reports

Patient history

A 73-year-old female patient presented with a debonded maxillary zirconia bridge supported by six implants placed five years earlier. Clinical and radiographic examination revealed mobility of four implants, associated pain, and significant peri- implantitis bone loss. One implant in the anterior maxilla was fractured.

Treatment planning

After discussion of all available treatment options—including extensive bone grafting combined with bilateral sinus floor elevation and prolonged healing periods— the patient elected to proceed with rehabilitation using the Bone Truss Bridge approach due to its reduced invasiveness and shorter treatment time.

Figure 1: Radiograph after debonding of the existing bridge.

Surgical procedure

Surgery was performed under local anesthesia.

Figure 2: Fractured implant at position 12.

Following removal of the failed implants at positions 22 and 23 and the fractured fixture at position 12 (Figure 2), a full-thickness flap was raised from the maxillary tuberosity to the anterior maxilla to expose the residual bone.

Figure 3: Extensive bone defect.

Figure 4: Limited crestal bone.

The presence of extensive bone defects (Figure 3) and insufficient crestal bone (Figure 4) precluded placement of conventional two-piece implants without grafting.

Figure 5: Fatty bone in the posterior maxilla.

Prior to placement of Pterygoid implants, the fatty bone (Figure 5) in the posterior maxilla is removed gain access to the pterygoid plates.

Figure 5: ROOTT P Diameter 3.5mm Length 20mm.

Posterior anchorage was achieved with bilaterally placed pterygoid implants (ROOTT Compressive P, 3.5 × 20 mm).

Figure 6: Hand drill.

All implants were inserted manually using a hand driver (Figure 6) to optimize tactile control and cortical engagement.

Figure 7: Final insertion torque of approximately 70 N·cm.

High primary stability was achieved in both pterygoid implants (Figure 7).

Additional compressive tissue level implants were placed as follows:

- ROOTT P One Piece implants (3.5 × 20 mm) in positions 18 and 28.

- ROOTT M Tissue level implants (3.5 × 14 mm) in positions 22, 21, 12, and 13

Figure 8: Additional Implants placed.

A total of six additional implants were placed: two Pterygoid implants and four tissue- level screw-retained implants. These implants feature compressive threads designed to achieve high primary stability. The single, continuous “one-point” thread design converts shear forces into compression and promotes corticalization of trabecular bone, stabilizing micromovement and supporting early loading (Figure 8).

Implant design rationale

Deep, aggressive compressive threads increase bone–implant contact and insertion torque, enhancing primary stability particularly in low-density bone [21]. Underprepared osteotomies combined with self-tapping compressive threads condense cancellous bone rather than cutting it away, creating a denser, cortical-like envelope around the implant [22].

The condensation and subsequent remodeling of trabecular bone into a more cortical structure (“corticalization”) reduces micromovement and improves resistance to functional loading [21]. A single continuous thread with increased depth and reduced pitch distributes forces over a larger surface area and shifts stress from shear to compression, which bone tolerates more favorably [21].

Compressive One-Piece Tissue-level implants with integrated abutments eliminate the micro-gap at bone level and reduce crestal bone resorption associated with pumping effects [22]. Tissue-level positioning combined with high primary stability enables predictable immediate or very early loading in full-arch protocols such as Bone Truss Bridge (BTB) in the atrophied maxillae.

Prosthetic phase

Figure 9: Impression procedure.

Following implant placement, screw-retained impression transfers were stabilized with bite registration material, and an analog impression was taken without a tray (Figure 9). A temporary fixed prosthesis was fabricated chairside and delivered on the day of surgery.

Figure 10: Soft-tissue condition after five days.

Figure 11: Verification jig.

Five days later, soft-tissue healing was satisfactory (Figure 10), and a verification jig was tried in to confirm accuracy and occlusion (Figure 11).

Figure 12: Framework try-in.

Seven days postoperatively, the metal framework and esthetic setup were evaluated for passive fit and appearance. (Figure 12).

Figure 13: Finished metal resin bridge.

Figure 14: Patient aesthetics.

The definitive screw-retained metal–resin prosthesis (Figure 13) was delivered approximately two weeks after surgery (Figure 14).

Outcome

Figure 15: Final Radiograph.

The patient experienced rapid functional and esthetic rehabilitation and reported high satisfaction with comfort, stability, and shortened treatment duration (Figure 15). No surgical or prosthetic complications were observed during the early follow-up period.

Discussion

This case illustrates two key clinical principles. First, the Bone Truss Bridge protocol expands treatment options for severely atrophic maxillae by providing a graftless, minimally invasive alternative to extensive augmentation or zygomatic implant solutions. Second, bone-driven implantology enables optimal use of native cortical bone, achieving high primary stability and predictable early loading while reducing morbidity, cost, and overall treatment time.

Although long-term, large-scale clinical data are still needed, early clinical evidence suggests that BTB designs may play an increasingly important role in the rehabilitation of compromised maxillae.

Conclusion

The Bone Truss Bridge approach enabled successful rehabilitation of a severely compromised maxilla within a significantly reduced timeframe compared with conventional graft-based protocols. In appropriately selected patients and when performed by experienced clinicians, this method represents a promising, patient- centered alternative for full-arch maxillary rehabilitation.

References

- Pavanelli ALR, de Avila ED, Barros-Filho LAB, Mollo Junior FA, Cirelli JA, et al. (2021) A prosthetic and surgical approach for full-arch rehabilitation in atrophic maxilla previously affected by peri-implantitis. Case Rep Dent. 2021:6654067.

- Esposito M, Felice P, Worthington HV. (2014) Interventions for replacing missing teeth: dental implants in zygomatic bone for the rehabilitation of the severely resorbed maxilla. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 5:CD004151.

- Pjetursson BE, Asgeirsson AG, Eliasson ST, Gunnarsson S. (2014) Ten-year survival rates of fixed partial dentures on implants: a systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 25(11):1199-210.

- Aparicio C, Manresa C, Francisco K, Aparicio A, Tallarico M, et al. (2014) Zygomatic implants: indications, techniques and outcomes, and the zygomatic success code. Periodontal. 66(1):41-58.

- Bedrossian E. (2010) Rehabilitation of the edentulous maxilla with the zygoma implant: health-related quality of life evaluation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 25(6):1213-21.

- Candel-Marti E, Carrillo-Garcia C, Penarrocha-Oltra D, Penarrocha-Diago M. (2012) Rehabilitation of atrophic posterior maxilla with zygomatic implants: review. J Oral Implantol. 38(5):653-7.

- Davó R, Malevez C, Rojas J, Rodríguez J, Regolf J. (2007) Clinical outcome of 124 non- submerged zygomatic implants: a 2-year follow-up study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 18(1):117-22.

- Agbaje JO, Diederich H. (2021) Bone Truss Bridge (BTB) approach for atrophic maxilla rehabilitation. J Oral Health Craniofac Sci. 6:014-022.

- Jensen OT, Adams MW. (2009) The case for zygomatic implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 67(11):12-22.

- Malo P, de Araujo Nobre M, Lopes A, Moss SM, Molina GJ. (2003) "All-on-4" immediate-function concept with Brånemark System implants for completely edentulous mandibles: a retrospective clinical study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 5(1):2-9.

- Aparicio C, Ouazzani W, Garcia R, Arevalo X, Muela A, et al. (2006) A prospective clinical study on titanium implants in the zygomatic bone for function of edentulous maxillae with pronounced resorption. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 8(3):114-22.

- Degidi M, Piattelli A, Gehrke P, Carinci F, Perrotti V. (2005) Immediate loading of self- tapping implants: a 6-month study of 260 implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 20(4):551-6.

- Frost HM. (1987) Bone "mass" and the "mechanostat": a proposal. Anat Rec. 219(1):1- 9.

- Misch CE. (1990) Density of bone: effect on treatment planning, surgical approach, and healing. Contemporary Implant Dentistry. St. Louis: CV Mosby Co; 1990:469-85.

- Trisi P, Rao W. (1999) Bone classification: clinical-histomorphometric comparison. Clin Oral Implants Res. 10(1):1-7.

- Brunski JB. (1992) Biomechanical factors affecting the bone-dental implant interface. Clin Mater. 10(3):153-201.

- Esposito M, Hirsch JM, Lekholm U, Thomsen P. (1998) Biological factors contributing to failures of osseointegrated oral implants. (I). Success criteria and epidemiology. Eur J Oral Sci. 106(1):527-51.

- Ericsson I, Nilson H, Lindh T, Nilner K, Randow K. (2000) Immediate functional loading of Brånemark single tooth implants. An 18 months' clinical pilot follow-up study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 11(1):26-33.

- Piattelli A, Paolantonio M, Corigliano M, Scarano A. (1997) Immediate loading of titanium plasma-sprayed screw-shaped implants in man: a clinical and histological report of two cases. J Periodontol. 68(6):591-7.

- Degidi M, Nardi D, Piattelli A. (2009) Immediate loading of the edentulous maxilla with a definitive restoration: a 1-year prospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 24(1):92-9.

- Haroyan H, Agbaje JO, Mansour AD, Lambrichts I, Politis C. (2018) A systematic review on pterygoid implants. J Oral Health Craniofac Sci. 3:024-033.

- Meningaud JP, Benadiba L, Guillot C, Bertrand J, Pelinaru G. (2010) The use of zygomatic implants for the rehabilitation of the severely resorbed maxilla. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 68(9):2208-13.

- Agbaje JO, Diederich H. (2017) Bone Truss Bridge: a new concept for rehabilitation of atrophic maxilla. Case Rep Dent. 2017:1042732.

- Agbaje JO, Diederich H. (2018) Evolution of the "Bone Truss Bridge" (BTB) technique for the rehabilitation of atrophic maxilla. Inter J Case Rep. 2:5.