Early Feasibility and Safety of a Placental Amnion Membrane as an Adjunct to Standard Care for Diabetic Foot Ulcers

Bruce Werber1, Krista Casazza2, Rob Bramblett2, Lora Harnack2 and Jonathan RT Lakey2,3*

1BioXtek, Pompano. Beach, FL

2Purity Health Inc, Nashville TN

3University of California, Irvine- Department of Surgery and Biomedical Engineering, Irvine CA

*Corresponding author: Jonathan RT Lakey, PhD, MSM Chief Scientific Advisor, Purity Health Inc, Nashville, TN, USA

Citation: Werber B, Casazza K, Bramblett R, Harnack L, Lakey JRT. Early Feasibility and Safety of a Placental Amnion Membrane as an Adjunct to Standard Care for Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Adv Clin Med Res. 6(3):1-12.

Received: January 16, 2026 | Published: January 28, 2026

Copyright© 2026 Genesis Pub by Werber B, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are properly credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.52793/ACMR.2026.7(1)-112

Abstract

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are a major cause of infection, amputation, and healthcare utilization. Despite guideline-based care incorporating debridement, infection surveillance, perfusion assessment, and offloading, healing remains variable and frequently prolonged. Placental-derived amnion membrane allografts may support wound repair by providing a biologically active extracellular matrix scaffold; however, prospective evidence in well-characterized DFU cohorts remains limited. This pre-interim analysis reports feasibility, baseline characteristics, treatment exposure, and early wound outcomes following adjunctive amnion membrane therapy. This is a prospective, single-arm clinical study evaluating an amnion membrane allograft applied as an adjunct to standard DFU care. Adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes and Wagner grade I–II DFUs located below the malleoli were eligible, with perfusion adequacy confirmed by protocol-defined criteria. Pre-interim analyses were descriptive, summarizing subject disposition, baseline demographics and ulcer characteristics, treatment exposure, and early wound outcomes (closure status, infection indicators). At data cutoff, 11 subjects were enrolled; 9/11 (82%) completed screening assessments and met eligibility criteria. Four subjects (36%) proceeded to treatment and constituted the treated analysis set. All treated subjects completed Visit 2 and at least one post-treatment follow-up visit, with no withdrawals or loss to follow-up observed to date. The treated cohort was male and comprised exclusively type 2 diabetes. Glycemic control was favorable (mean HbA1c ~6.4%). Baseline ulcers were neuropathic/non-ischemic in profile and consistent with typical DFU trial populations (Wagner grade I–II; mean baseline area 2.8 cm², range 1.8–5.5 cm²).

Subjects received 1–3 amnion applications (median 2) with protocolized standard wound care and offloading. No complete wound closures were observed during early follow-up (approximately 2–4 weeks), and ulcers remained open at last observation; clinical signs of infection were infrequent, and no deterioration requiring discontinuation occurred. No safety concerns, infection-related deterioration, or early wound worsening were observed during the pre-interim follow-up window. Study procedures and protocol adherence were feasible in an outpatient DFU setting. Definitive assessment of healing effectiveness endpoints (including 12-week closure and time-to-closure) awaits completion of enrollment and longer follow-up.

Keywords

Diabetic foot ulcer; Amnion membrane; Placental membrane allograft; Wound healing; Biological dressings; Feasibility study.

Introduction

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are among the most serious and costly complications of diabetes mellitus, affecting an estimated 19–34% of individuals with diabetes during their lifetime and contributing substantially to infection-related hospitalizations, lower extremity amputation, and premature mortality [1,2]. The pathogenesis of DFU non-healing is multifactorial and reflects a convergence of peripheral neuropathy, microvascular and macrovascular dysfunction, immune impairment, and sustained inflammatory signaling; hyperglycemia further exacerbates these processes through endothelial injury, impaired collagen synthesis, altered leukocyte function, and dysregulation of growth factor activity [3-5]. In parallel, delayed presentation and inequities in access to multidisciplinary limb-preservation care contribute to advanced wound severity and worse outcomes, reinforcing DFUs as a chronic disease state with high clinical and economic burden [2,3,6]. Standard DFU care is guideline-driven and includes sharp debridement, structured infection surveillance, objective assessment of perfusion, and mechanical offloading to reduce plantar pressure and tissue stress [7,8]. Despite these foundational measures, healing remains inconsistent in real-world practice, and a substantial proportion of ulcers fail to achieve timely closure. Consequently, biologic adjuncts intended to modulate the wound microenvironment and support tissue repair (e.g., placental membrane allografts) have gained increasing attention [9]. Placental-derived extracellular matrix (ECM) tissues contain structural proteins and bioactive mediators that may provide a topical scaffold to promote re-epithelialization while exerting immunomodulatory and antimicrobial effects [10]. However, outcomes vary across products, application schedules, and study designs, a and comparative effectiveness across heterogeneous DFU populations remains incompletely defined.

Given these gaps, there is an ongoing need for prospective clinical evidence evaluating placental membrane therapies within well-characterized DFU cohorts, with standardized offloading, perfusion assessment, and wound documentation. The overarching objective of the present study is to evaluate the safety, feasibility, and early effectiveness of an amnion membrane product applied as an adjunct to standard DFU care. This report presents pre-interim results from an ongoing perspective clinical study, focusing on patient disposition, baseline cohort characteristics, treatment exposure, safety signals, and early wound outcomes. Historical benchmarks from published literature are used to provide context for observed healing trajectories and complication rates, recognizing that definitive comparative inference requires completion of follow-up and formal endpoint ascertainment.

Methods

Study design and setting

This is a prospective, single-arm clinical study evaluating an amnion membrane allograft as an adjunct to standard wound care for diabetic foot ulcers. The study is being conducted at one outpatient wound care center in the United States. The protocol was approved by a centralized Institutional Review Board (IRB) prior to initiation, and all subjects provided written informed consent before undergoing study-related procedures. The current report is a pre-interim analysis based on data available through December 2025 and therefore reflects an incomplete dataset with ongoing follow-up and continued enrollment.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Eligible participants were adults aged ≥18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus and a target DFU located below the malleoli. The target ulcer was required to meet the following criteria:

- Post-debridement ulcer area between 1.0 cm² and 20.0 cm² measured at screening using the eKare wound assessment device,

- Ulcer duration of ≥4 weeks and ≤12 [weeks/months as per protocol] at screening,

- Wagner grade I or II without exposed tendon, muscle, bone, or joint capsule,

- Adequate limb perfusion confirmed by at least one of the following documented measures: ankle–brachial index (ABI) within protocol-defined limits, toe pressure ≥40 mmHg, toe–brachial index ≥0.65, or transcutaneous oxygen pressure (TcPO₂) ≥30 mmHg.

If more than one ulcer was present, the target ulcer was required to be at least 2 cm from the nearest edge of any adjacent ulcer.

Exclusion criteria

Key exclusion criteria included:

- HbA1c >10% at screening,

- Active infection of the target ulcer or suspicion of osteomyelitis, cellulitis, or gangrene,

- Wagner grade III or higher,

- Current dialysis or planned initiation of dialysis,

- Pregnancy or lactation,

- Use of advanced biologic DFU therapies (including other amniotic/umbilical cord products, growth factors, living skin equivalents, dermal substitutes, or enzymatic debriders) within 30 days prior to screening,

- Current use of topical antimicrobial or silver-containing products,

- Prior application of any placental membrane product to the target ulcer,

- Participation in another investigational study within 30 days prior to screening.

Study procedures

Screening and Baseline Assessment

At screening, informed consent was obtained and eligibility was confirmed. Baseline demographic and clinical data were collected, including diabetes type, duration, tobacco use, and relevant medical history. Vital signs were recorded, and perfusion adequacy was documented based on ABI or other validated metrics per protocol. Baseline ulcer characteristics were assessed, including ulcer location, duration, Wagner grade, and post-debridement area measured with the eKare device. Standard wound care, including sharp debridement when indicated, was performed.

Treatment intervention

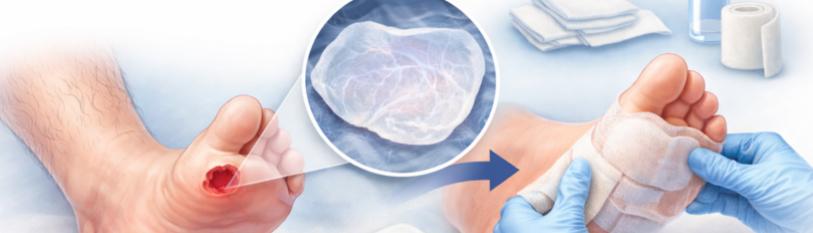

At Visit 2 (study day 1), eligible subjects received application of the study amnion membrane product to the target ulcer. Patch size was selected based on ulcer dimensions (e.g., 2×3 cm, 4×4 cm). Application was performed by trained clinicians in accordance with the protocol. Subsequent applications were permitted at protocol-defined intervals based on wound status and investigator discretion, and treatment exposure (number of applications, patch sizes, and dates) were recorded. The investigational membrane is a dehydrated human amniotic membrane–derived extracellular matrix allograft intended to serve as a topical biologic scaffold when used in conjunction with standard DFU care. The investigational product was a placental amnion membrane allograft (BX-PM) applied as a conformable patch in either single-layer (Sanoplast ECM) or tri-layer (Xceed TL Matrix, a.k.a. Sanoplast Tri) configurations, with patch size selected to fully cover the post-debridement ulcer surface without overlap beyond the wound margin.

Standard of care co-interventions

All subjects received standard DFU care throughout the study, including:

- Debridement as clinically indicated,

- Protocol-specified dressing regimens (non-adherent contact layers, foam/alginate/hydrofiber as appropriate),

- Provision of sponsor-approved offloading devices (e.g., walker boot) and standardized patient education regarding offloading adherence and dressing care.

Follow-up visits

Subjects were evaluated at follow-up visits per protocol schedule (e.g., every 2 weeks ± allowable window). At each follow-up, investigators assessed:

- Wound status including evidence of complete closure,

- Clinical signs and symptoms of infection,

- Debridement performance and dressing application details,

- Compliance of offloading since the prior visit,

- Concomitant medication changes, adverse events, and protocol deviations.

Outcomes

Primary Outcomes (Pre-Interim Report). Given the pre-interim nature of this analysis, the primary outcomes were feasibility and early clinical course, including:

- Study feasibility and completeness: proportion completing screening, baseline treatment visit, and follow-up visits.

- Safety and tolerability: incidence of reported adverse events and serious adverse events; frequency of infection signs at the target ulcer.

- Early wound outcome status: proportion of wounds closed at each completed visit and proportion remaining open at last observed visit.

Secondary/Exploratory outcomes

Exploratory outcomes included descriptive characterization of treatment exposure (number of applications), protocol deviations, offloading compliance, and clinically significant laboratory abnormalities (including HbA1c and investigator-reported significance).

Because this is a single-arm cohort, no concurrent control arm is included. To contextualize observed early healing and complication rates, historical benchmarks were drawn from contemporary DFU literature and guideline-based reviews describing DFU incidence, pathophysiology, and standard wound care outcomes, including expected healing timeframes and infection rates under standard care. These historical references were used descriptively and were not intended for formal statistical inference.

Statistical analysis

All analyses are descriptive. Continuous variables are summarized using mean ± standard deviation and median (interquartile range) as appropriate; categorical variables are summarized using counts and percentages. Outcomes are reported as observed cases without imputation for missing data, and the denominator for each visit-level outcome reflects the number of subjects with available data at that timepoint.

This analysis is not intended to assess comparative effectiveness, establish Medicare coverage eligibility, or support reimbursement claims; rather, it establishes feasibility, safety, and methodological rigor to support subsequent analyses of protocol-defined healing endpoints after completion of enrollment and follow-up.

Data management and quality assurance

Study data were entered into an electronic data capture (EDC) system by trained personnel. Data for these analyses were extracted on December 22, 2025, and include all forms entered through that cut date. Consistency checks were performed to identify missing or implausible values.

Results

Study disposition and analysis populations

A total of 11 subjects were enrolled at the time of this pre-interim data cutoff (Table 1). Screening case report forms were completed for 9/11 subjects (82%), and these individuals met eligibility criteria to continue per investigator assessment. Four subjects (4/11; 36%) proceeded to randomization and received the study amnion membrane product, comprising the treated analysis set. All treated subjects attended Visit 2 (baseline treatment visit) and completed at least one post-treatment follow-up visit, yielding a 100% follow-up rate within the treated set at the time of this analysis. Two treated subjects had completed Visit 4, reflecting approximately four weeks of follow-up, while the remaining treated subjects were in earlier follow-up windows. No withdrawals or loss to follow-up were recorded in the treated cohort as of the data cutoff.

|

Study stage |

N |

% of enrolled |

|

Enrolled subjects |

11 |

100 |

|

Screening CRF completed |

9 |

82 |

|

Eligible per protocol |

9 |

82 |

|

Randomized / treatment assigned* |

4 |

36 |

|

Received ≥1 amnion membrane application |

4 |

36 |

|

Completed Visit 2 (baseline treatment visit) |

4 |

36 |

|

Completed ≥1 post-treatment follow-up visit |

4 |

36 |

|

Completed Visit 4 (~4 weeks) |

2 |

18 |

|

Withdrawn / lost to follow-up |

0 |

0 |

*The treated set includes all subjects who received ≥1 amnion membrane application and attended Visit 2.

Table 1: Subject disposition and analysis populations.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the treated cohort are summarized in (Table 2). All treated subjects were male and had type 2 diabetes mellitus. Glycemic control was generally favorable, with a mean HbA1c of approximately 6.4% (SD ~0.4%) among treated subjects. Tobacco exposure was minimal, with no current tobacco use reported. A history of hypertension was present in approximately half of the subjects treated, and several participants were receiving glucose-lowering agents.

|

Characteristic |

Amnion membrane cohort (n=4) |

|

Sex, male |

100% |

|

Mean age (+SD), years |

58.7+12.0 |

|

Diabetes type (Type 2) |

100% |

|

Duration of diabetes, years |

10–30 (range) |

|

HbA1c, % |

Mean ± SD: 6.4 ± 0.4 |

|

Tobacco use (current) |

0% |

|

Hypertension history |

50% |

Table 2:

Target ulcer characteristics are reported in (Table 3). All treated ulcers were located on the plantar surface or heel and met protocol-defined Wagner grade criteria (grade I–II). Baseline ulcer size at screening was modest, with a mean area of 2.8 cm² (range 1.8 to 5.5 cm²). All treated subjects underwent baseline debridement. Perfusion parameters met eligibility criteria, with ankle–brachial index (ABI) values indicated adequate perfusion in the treated cohort, with a mean ABI of 1.14 (range, 1.11–1.17). The cohort was characterized by single target ulcers without adjacent ulcers within 2 cm and no evidence of multiple ulcers on the same affected foot among treated subjects.

|

Ulcer characteristic |

Amnion membrane cohort (n=4) |

|

Ulcer location (plantar or heel) |

100% |

|

Ulcer duration, weeks |

~8–24 |

|

Wagner grade I–II |

100% |

|

Baseline ulcer area, cm² |

Mean ± SD: 2.8 ± 1.81 cm² |

|

Median (range): 1.95 (1.8–5.5) cm² |

|

|

Multiple ulcers on same foot |

0% |

|

ABI within inclusion range |

100% |

|

Baseline debridement performed |

100% |

|

Offloading device provided |

75% |

Table 3:

Treatment delivery and adherence are summarized in (Table 4). Participants received either a single-layer or tri-layer amnion membrane configuration, with patch sizes selected based on wound dimensions (commonly 2×3 cm or 4×4 cm). The number of applications per subject ranged from 1 to 3, with a median of 2 applications during the observed follow-up interval. Re-application was documented at follow-up visits as clinically indicated. Standard wound care co-interventions, including debridement, protocol-directed dressings, and offloading recommendations, were implemented. Most treated subjects received a sponsor-approved offloading device, and reported non-compliance was uncommon. No protocol deviations were recorded in the treated cohort during the period captured in this pre-interim dataset.

|

Parameter |

Amnion membrane cohort |

|

Amnion product type |

Single-layer or tri-layer |

|

Patch size range |

2×3 cm to 4×4 cm |

|

Applications per subject |

Median 2 (range 1–3) |

|

Re-application at follow-up visits |

Yes (Visit 3–4) |

|

Concomitant standard wound care |

Debridement + dressings |

|

Offloading compliance (reported) |

High; non-compliance rare |

|

Protocol deviations |

None reported |

Table 4: Treatment exposure and protocol adherence.

Early wound outcome status is summarized in (Table 5). At the time of analysis, no treated subjects achieved complete wound closure through the latest completed follow-up visit, and all treated ulcers remained open at last observation. Clinical signs of infection were infrequently reported, and no evidence of deterioration requiring study discontinuation was observed during the current follow-up window. Follow-up duration in the treated cohort ranged from approximately two to four weeks, with two subjects reaching Visit 4 (approximately four weeks post-baseline).

|

Outcome |

Amnion membrane cohort |

|

Complete closure by ~4 weeks |

0/4 (0%) |

|

Ulcers remaining open at last visit |

100% |

|

Clinical signs of infection |

Rare |

|

Early wound stability (no deterioration) |

100% |

|

Follow-up duration, days |

~14–28 |

Table 5: Early effectiveness and wound status outcomes.

Discussion

This analysis provides an early characterization of feasibility, baseline cohort comparability to typical DFU trial populations, and short-term clinical course following adjunctive amnion membrane application in individuals with DFUs. Several findings are noteworthy. First, despite limited follow-up (approximately 2–4 weeks among treated subjects), the treated cohort demonstrated complete retention and visit adherence, with no documented withdrawals or loss to follow-up to date. Second, the cohort had baseline ulcer characteristics consistent with populations commonly enrolled in DFU adjunctive therapy trials (e.g., neuropathic, non-ischemic, Wagner grade I–II ulcers of moderate size) indicating clinical relevance and applicability in real-world settings. Third, while no complete closures were observed during early follow-up, this is consistent with expected DFU healing timelines and does not, in isolation, indicate lack of therapeutic effect. Importantly, the cohort demonstrated an early clinical signal of wound stability without deterioration or infection-related complications, which is particularly relevant given that infection and worsening are frequent drivers of attrition and poor outcomes in DFU populations [11].

Complete epithelialization in DFU populations typically occurs over 6–12 weeks, even under optimized multidisciplinary care and use of advanced wound therapies [4,5,12,13], and real-world cohorts evaluating dehydrated amniotic membrane adjuncts similarly report median closure times near 9 weeks, even when early area reduction is observed [14]. Accordingly, the absence of early closure in this pre-interim dataset should be interpreted within the context of expected DFU biology and the well-established temporal dynamics of healing. In both standard-of-care (SOC) cohorts and interventional trials, meaningful separation between treatment strategies often becomes apparent later in the follow-up period, particularly when complete closure is used as the endpoint [2,15]. This is reinforced by guideline recommendations that focus on early improvement metrics (e.g., percent area reduction within 4 weeks) as a decision point for escalation or reassessment rather than expecting early closure [16,17]. Accordingly, early stabilization and avoidance of infection are clinically meaningful. DFUs that remain open longer are at sustained risk for infection, hospitalization, and amputation [7,18]. The current cohort demonstrated no infection-related deterioration in the short follow-up interval captured, supporting feasibility and early tolerability of the intervention within structured wound care.

Recent real-world evidence further supports that separation in healing trajectories with dehydrated amniotic membrane adjuncts often becomes evident after multiple applications and later follow-up. In a retrospective single-provider cohort study evaluating adjunctive dehydrated human acellular amniotic membrane (Sanoplast®), Bowlin et al [14]. reported a median wound area reduction to 47% of baseline after two applications and a per-protocol 12-week closure rate of 69%, compared with 47% under standard dressing care alone; median time to closure was 9.0 weeks versus 13.3 weeks, with no treatment-related adverse events observed. These findings, although retrospective and subject to confounding, support the expectation that clinically meaningful healing endpoints require longer observation windows than the 2–4 weeks captured in the present pre-interim cohort.

A key strength of this analysis is excellent adherence and retention within the treated cohort. Attrition rates in DFU trials commonly range from 20% to 40% by 12 weeks, driven by infection, hospitalization, competing comorbidities, and non-adherence to offloading or visit schedules [19]. Early retention is therefore informative, particularly in pragmatic clinical settings where DFU patients often have high healthcare utilization and complex social determinants influencing follow-up [20]. The current findings suggest that the intervention and study procedures are operationally feasible and acceptable to participants. This represents an essential prerequisite for later-stage effectiveness evaluation and for generating interpretable longitudinal outcomes.

The treated cohort demonstrated relatively good glycemic control, with HbA1c values at the lower end of ranges typically reported in DFU cohorts. Hyperglycemia is strongly associated with impaired wound healing, increased infection risk, and higher amputation rates via mechanisms including leukocyte dysfunction, endothelial injury, and impaired collagen synthesis [5,9,11,19,21]. Observational data consistently demonstrate that elevated HbA1c correlates with worse DFU severity and poorer limb outcomes [22–25]. The favorable glycemic status in this cohort may reduce the risk of early infectious complications and support tissue repair processes, potentially improving the probability of eventual closure. However, this same feature may also limit generalizability to higher-risk DFU populations with poorer metabolic control. Therefore, subsequent analyses should stratify outcomes by glycemic status (e.g., HbA1c <7.5% vs ≥7.5%) and incorporate changes in glycemic management during follow-up.

Baseline wound characteristics in this cohort are consistent with inclusion criteria commonly used in DFU interventional trials and guideline-informed trial design [26]. These factors enhance interpretability and strengthen the rationale for contextualizing outcomes using historical benchmarks. In DFU trials, perfusion adequacy is crucial because ischemia is a dominant predictor of non-healing and confounds interpretation of biologic therapies8. Similarly, ulcer depth and infection status strongly influence healing probability and are typically controlled via inclusion criteria. Notably, the broader DFU literature increasingly emphasizes glycemic optimization as a cornerstone of management, in addition to local wound care measures [27]. The metabolic profile of this cohort may provide a favorable platform in which local biologic therapies can exert additive benefits, but this will require confirmation with longer follow-up and standardized endpoints.

Placental-derived allografts provide a biologically plausible adjunct to DFU management. These products contain ECM components and bioactive factors that may support angiogenesis, modulate inflammation, and provide a scaffold for epithelialization [28-30]. Several randomized trials have demonstrated improved DFU closure rates with dehydrated amnion/chorion membrane constructs compared with SOC, particularly over 12-week horizons [31]. Systematic reviews similarly conclude that amnion membrane therapies can improve healing outcomes compared with SOC in selected DFU populations, although heterogeneity in products, application schedules, and trial designs limits definitive cross-product conclusions.

The present analysis does not yet provide sufficient duration to evaluate closure rates or sustained healing, but the documented absence of deterioration and the feasibility of repeated application align with the broader experience of placental membrane use in DFU treatment. Importantly, infection surveillance and offloading remain critical; advanced therapies are unlikely to overcome inadequate offloading, unresolved ischemia, or poor metabolic control [4,5,11,17–19,21,23].

Although complete closure was not observed, early stability without infection is clinically meaningful. Infection is a major determinant of DFU morbidity and drives hospitalization and amputation risk. The 2023 IWGDF/IDSA guideline emphasizes early identification and management of infection and notes that deterioration or failure to improve should trigger reassessment of vascular status and treatment strategy [32]. Similarly, the IWGDF offloading guideline underscores that offloading mechanical tissue stress is among the most important interventions for healing [32]. These guideline perspectives support the interpretation that early safety, stability, and adherence are foundational signals prior to evaluating later healing endpoints.

This analysis has several limitations inherent to a pre-interim dataset. The sample size is small, follow-up is short, and the study is single arm, limiting causal inference. The literature demonstrates wide variability in healing rates even under SOC, influenced by baseline ulcer area, duration, comorbidities, and offloading fidelity. In a recent meta-analysis of SOC healing rates of approximately 31% at 20 weeks were reported, underscoring that chronic DFUs frequently remain unhealed despite optimized SOC [33]. These data reinforce the need for adjunctive strategies, including biologics such as placental membrane allografts, while also illustrating why early closure is not expected. Additionally, while complete closure is captured as a binary outcome, quantitative wound area trajectories beyond baseline are not yet available in the current export, limiting assessment of percent area reduction (PAR) at four weeks, a validated surrogate marker of eventual healing. In a large prospective trial, percent change in wound area at four weeks was a robust predictor of complete healing at 12 weeks, and lack of ≥50% PAR by four weeks is commonly used as a trigger for treatment reassessment [34]. eKare-derived wound area assessments at each visit remains critical for analyses and to align with established DFU trial endpoints and guideline recommendations. Despite these limitations, the findings support continued enrollment and follow-up, with feasibility, retention, and early stability providing a foundation for later evaluation of closure rates, time-to-healing, and complication outcomes.

Planned analyses and evidence development pathway

Planned analyses will include (1) completion of target enrollment per protocol; (2) assessment of complete wound closure through 12 weeks using protocol-defined criteria, including confirmation of durable epithelialization; (3) longitudinal percent area reduction (PAR) analyses at 4 weeks and subsequent visits using eKare-derived planimetry, consistent with validated DFU response thresholds; (4) time-to-closure analyses and characterization of treatment exposure (number and frequency of applications); (5) prespecified descriptive and risk-adjusted benchmarking against published DFU cohorts matched on baseline wound size, duration, Wagner grade, and perfusion adequacy; and (6) comprehensive safety reporting including infection events, serious adverse events, and discontinuations.

References

- Akkus G, Sert M. (2022) Diabetic foot ulcers: A devastating complication of diabetes mellitus continues non-stop in spite of new medical treatment modalities. World J Diabetes. 13(12):1106-1121.

- McDermott K, Fang M, Boulton AJM, Selvin E, Hicks CW. (2023) Etiology, Epidemiology, and Disparities in the Burden of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care. 46(1):209-21.

- Da Silva J, Leal EC, Carvalho E, Silva EA. (2023) Innovative Functional Biomaterials as Therapeutic Wound Dressings for Chronic Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Int J Mol Sci. 24(12):9900.

- Armstrong DG, Tan TW, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. (2023) Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Review. JAMA. 330(1):62-75

- Deng L, Du C, Song P. (2021) The Role of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Diabetic Wound Healing. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021:8852759.

- Khaleel M, Garlapaty A, Hawkins S, Cook JL, Schweser K, et al. (2024) Association of Race with Referral Disparities for Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers at an Institution Serving Rural and Urban Populations. Foot Ankle Orthop. 9(3):24730114241281335.

- Gallagher KA, Mills JL, Armstrong DG. (2024) Current Status and Principles for the Treatment and Prevention of Diabetic Foot Ulcers in the Cardiovascular Patient Population: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 149(4):e232-e253.

- Aditya C, Bukke SPN, Anitha K, et al. (2025) A comprehensive review on diabetic foot ulcer addressing vascular insufficiency, impaired immune response, and delayed wound healing mechanisms. Front Pharmacol. 16:1622055.

- Abdelhakim M, Ogawa R. (2025) Emerging Therapies in Chronic Wound Healing: Advances in Stem Cell Therapy, Growth Factor Modulation, Mechanical Strategies and Adjuvant Interventions. Dermatol Ther. 15(12):3533-45.

- Protzman NM, Mao Y, Long D, et al. (2023) Placental-Derived Biomaterials and Their Application to Wound Healing: A Review. Bioeng Basel Switz. 10(7):829.

- Mohammad Zadeh M, Lingsma H, van Neck JW, Vasilic D, van Dishoeck AM. (2019) Outcome predictors for wound healing in patients with a diabetic foot ulcer. Int Wound J. 16(6):1339-46.

- Sheehan P, Jones P, Caselli A, Giurini JM, Veves A. (2003) Percent change in wound area of diabetic foot ulcers over a 4-week period is a robust predictor of complete healing in a 12-week prospective trial. Diabetes Care. 26(6):1879-1882.

- Armstrong DG, Lavery LA. (2005) Diabetic Foot Study Consortium. Negative pressure wound therapy after partial diabetic foot amputation: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 366(9498):1704-10.

- Bowlin C, Pearce M, Morsci NS. (2025) Accelerated Healing of Diabetic and Venous Ulcers with Adjunctive Dehydrated Human Amniotic Membrane: A Real-World Retrospective Cohort Study from a Single-Provider Practice. Adv Clin Med Res. 6(2):1-11.

- Frykberg RG, Tunyiswa Z, Weston WW. (2024) Retention processed placental membrane versus standard of care in treating diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 21(10):e70096.

- Patry J, Tourigny A, Mercier MP, Dionne CE. (2021) Quality of Diabetic Foot Ulcer Care: Evaluation of an Interdisciplinary Wound Care Clinic Using an Extended Donabedian Model Based on a Retrospective Cohort Study. Can J Diabetes. 45(4):327-333.e2.

- Patry J, Tourigny A, Mercier MP, Dionne CE. (2021) Outcomes and prognosis of diabetic foot ulcers treated by an interdisciplinary team in Canada. Int Wound J. 18(2):134-46.

- Cortes-Penfield NW, Armstrong DG, Brennan MB. (2023) Evaluation and Management of Diabetes-related Foot Infections. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 77(3):e1-e13.

- Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. (2017) Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N Engl J Med. 376(24):2367-75.

- Swaminathan N, Awuah WA, Bharadwaj HR. (2024) Early intervention and care for Diabetic Foot Ulcers in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Addressing challenges and exploring future strategies: A narrative review. Health Sci Rep. 7(5):e2075.

- Burgess JL, Wyant WA, Abdo Abujamra B, Kirsner RS, Jozic I. (2021) Diabetic Wound-Healing Science. Med Kaunas Lith. 57(10):1072.

- Akyüz S, Bahçecioğlu Mutlu AB, Guven HE, Başak AM, Yilmaz KB. (2023) Elevated HbA1c level associated with disease severity and surgical extension in diabetic foot patients. Ulus Travma Ve Acil Cerrahi Derg Turk J Trauma Emerg Surg TJTES. 29(9):1013-1018.

- Arya S, Binney ZO, Khakharia A. (2018) High hemoglobin A1c associated with increased adverse limb events in peripheral arterial disease patients undergoing revascularization. J Vasc Surg. 67(1):217-228.e1.

- Williams-Reid H, Johannesson A, Buis A. (2025) Wound management, healing, and early prosthetic rehabilitation: Part 3 - A scoping review of chemical biomarkers. Can Prosthet Orthot J. 8(1):43717.

- Farooque U, Lohano AK, Hussain Rind S. (2020) Correlation of Hemoglobin A1c With Wagner Classification in Patients with Diabetic Foot. Cureus. 12(7):e9199.

- Ganesan O, Orgill DP. (2024) An Overview of Recent Clinical Trials for Diabetic Foot Ulcer Therapies. J Clin Med. 13(24):7655.

- Doğruel H, Aydemir M, Balci MK. (2022) Management of diabetic foot ulcers and the challenging points: An endocrine view. World J Diabetes. 13(1):27-36.

- Protzman NM, Mao Y, Long D. (2023) Placental-Derived Biomaterials and Their Application to Wound Healing: A Review. Bioeng Basel Switz. 10(7):829.

- Tettelbach WH, Cazzell SM, Hubbs B, Jong JLD, Forsyth RA, et al. (2022) The influence of adequate debridement and placental-derived allografts on diabetic foot ulcers. J Wound Care. 31(9):16-26.

- Ingraldi AL, Audet RG, Tabor AJ. (2023) The Preparation and Clinical Efficacy of Amnion-Derived Membranes: A Review. J Funct Biomater. 14(10):531.

- Cazzell SM, Caporusso J, Vayser D, Davis RD, Alvarez OM, et al. (2024) Dehydrated Amnion Chorion Membrane versus standard of care for diabetic foot ulcers: a randomised controlled trial. J Wound Care. 33(7):4-14.

- Litvinenková V, Hlavacka F, Krizková M. (1980) Postural control related to the different tilting body positions. The Physiologist. 23(6):153-54.

- Coye TL, Bargas Ochoa M, Zulbaran-Rojas A. (2025) Healing of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers receiving standard treatment in randomised controlled trials: A random effects meta-analysis. Wound Repair Regen Off Publ Wound Heal Soc Eur Tissue Repair Soc. 33(1):e13237.

- Snyder RJ, Cardinal M, Dauphinée DM, Stavosky J. (2010) A post-hoc analysis of reduction in diabetic foot ulcer size at 4 weeks as a predictor of healing by 12 weeks. Ostomy Wound Manage. 56(3):44-50.